Counter-Errorist

THINK TANK

If you love rockets, you can’t help but notice that real space launch vehicles lift off the pad slowly,but model rockets zip up like darts. That’s how I became obsessed with using thrust vector control (TVC) — gimbaling the rocket motor — instead of fins to keep model rockets upright, so they can launch, and land, far more realistically.

ZERO TO ROCKETEER

I started out from scratch in rocketry; I’m all self-taught. After graduating with a degree in audio engineering from Berklee College of Music in 2014, I saw what SpaceX and other aerospace companies were going for with propulsive landing technology and I was hooked. I knew I wanted to get into rocketry to get a job at one of these companies, and I wasn’t in a position to pay for another college degree. I figured instead I could demonstrate what I was teaching myself by propulsively landing a model rocket the same way SpaceX landed the Falcon 9. It was a literal “shower idea.”

I started BPS in 2015 with the goal of achieving vertical takeoff and vertical landing (VTVL) of a scale model Falcon 9 rocket. This would require me to solve two tough problems — thrust-vectored flight and propulsive landings — using solid-fuel hobby rocket motors.

I picked up a few textbooks (I strongly recommend Rocket Propulsion Elements by George Sutton and Structures by J.E. Gordon), found a few good YouTube tutorials for coding and mechanical design, and got to work experimenting.

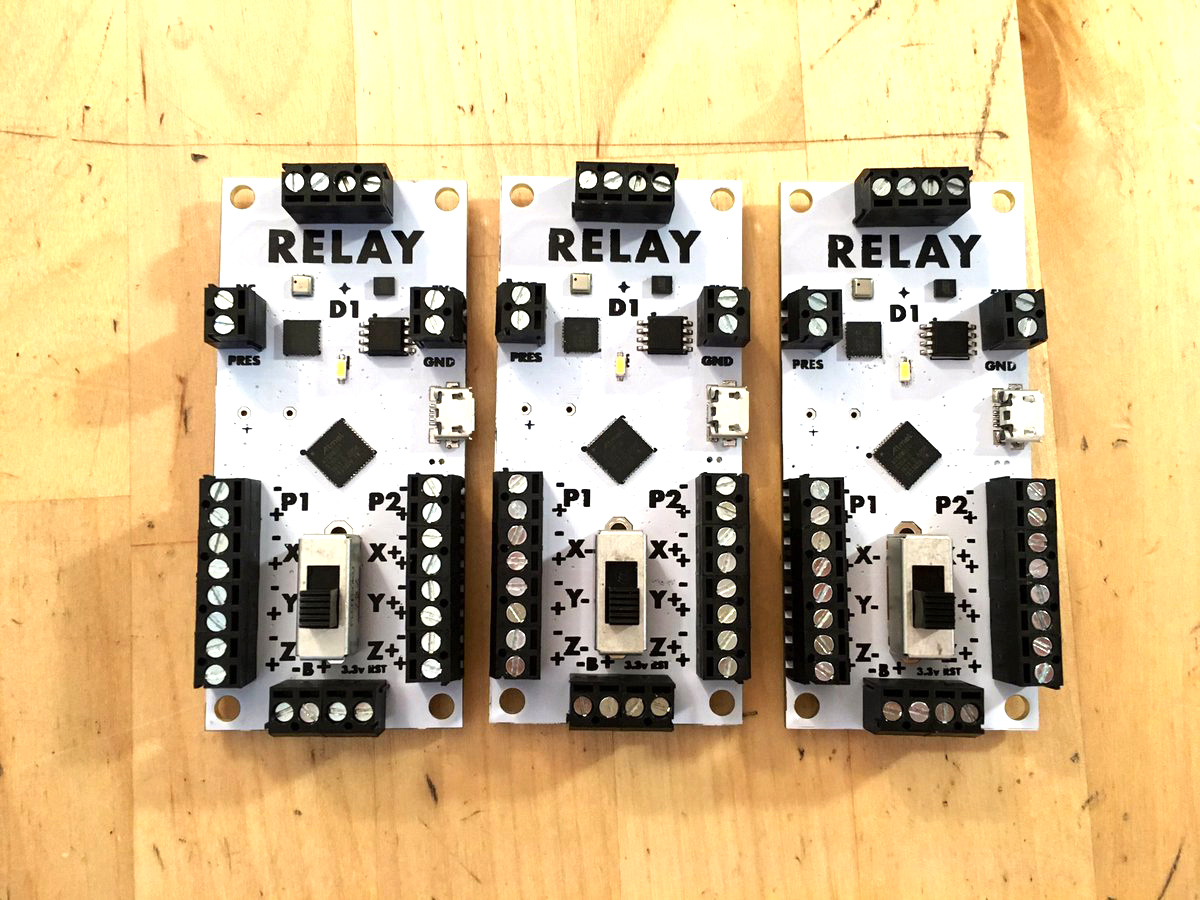

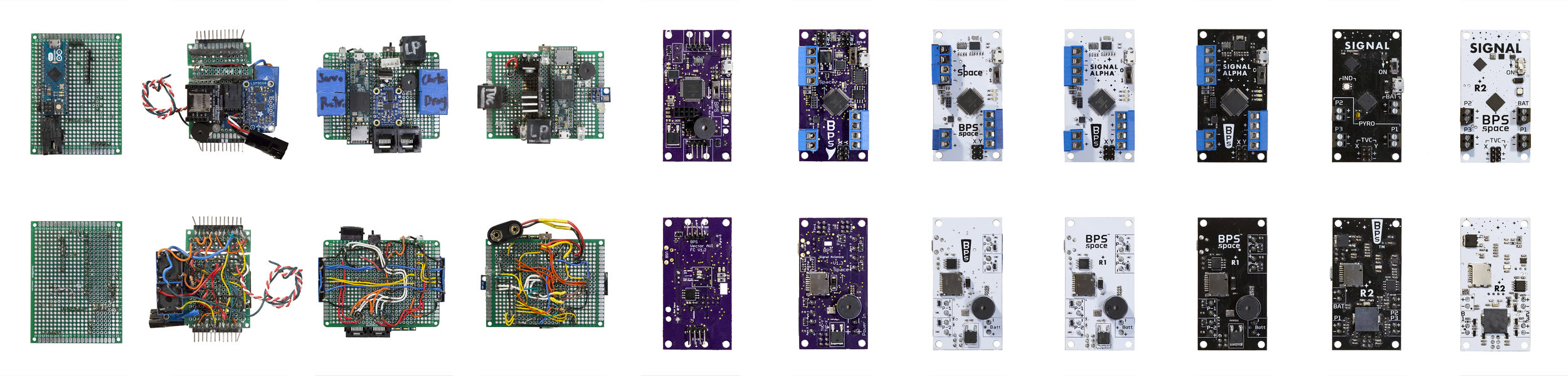

BPS has produced a lot of rocketry flight computers. Like maybe way too many. Here they are in chronological order.

I naïvely thought it would take four months. My first ten launches were failures. But the eleventh succeeded, and the successes accelerated after that. After four years of hard work, crashes, and iterative designs, I’m now achieving beautiful thrust-vectored launches of several rockets, including my 1:48-scale Falcon Heavy — three cores! — that you can watch on my YouTube channel.

And after some very near misses, I’m confident my Echo rocket will stick the vertical landing in 2019. Rather than attempt to throttle a solid-fuel motor, I’m firing the entire retro motor —also TVC’ed —at the precise time and altitude to enable a soft touchdown. It hasn’t been easy.

KITS FOR MAKERS

Of course this technology is still not mature, and it’s my hope that the advanced model rocketry community will build upon what I’ve done. In 2017, I began selling my Signal flight computer board and TVC motor mount together in a kit. After getting user feedback, the computer was redesigned from the ground up to include Bluetooth — Mission Control from your phone!

BPS.space is now a proper company and a full-time job for me, funded through flight computer sales, the BPS.space Patreon page, YouTube ad revenue, and sponsorships.

This kit is for advanced rocketeers. If you don’t have experience with scratch-built rockets, I recommend you hone your skills first with an Estes ready-to-fly kit and seek advice from fellow rocketeers at the National Association of Rocketry Facebook Group and the Rocketry Subreddit.

And if you’ve got some experience, I hope you’ll give it a try! I’ve even shared a scale model of the Rocket Lab Electron you can build using my tutorials.

THRUST VECTOR CONTROL – Ready to Aim Fire

Model rockets have fins and launch quickly, but real space launch vehicles don’t; they actively aim — vector — their rocket exhaust to steer the rocket. With thrust vectoring, your model rockets can slowly ascend and build speed like the real thing, instead of leaving your sight in seconds.

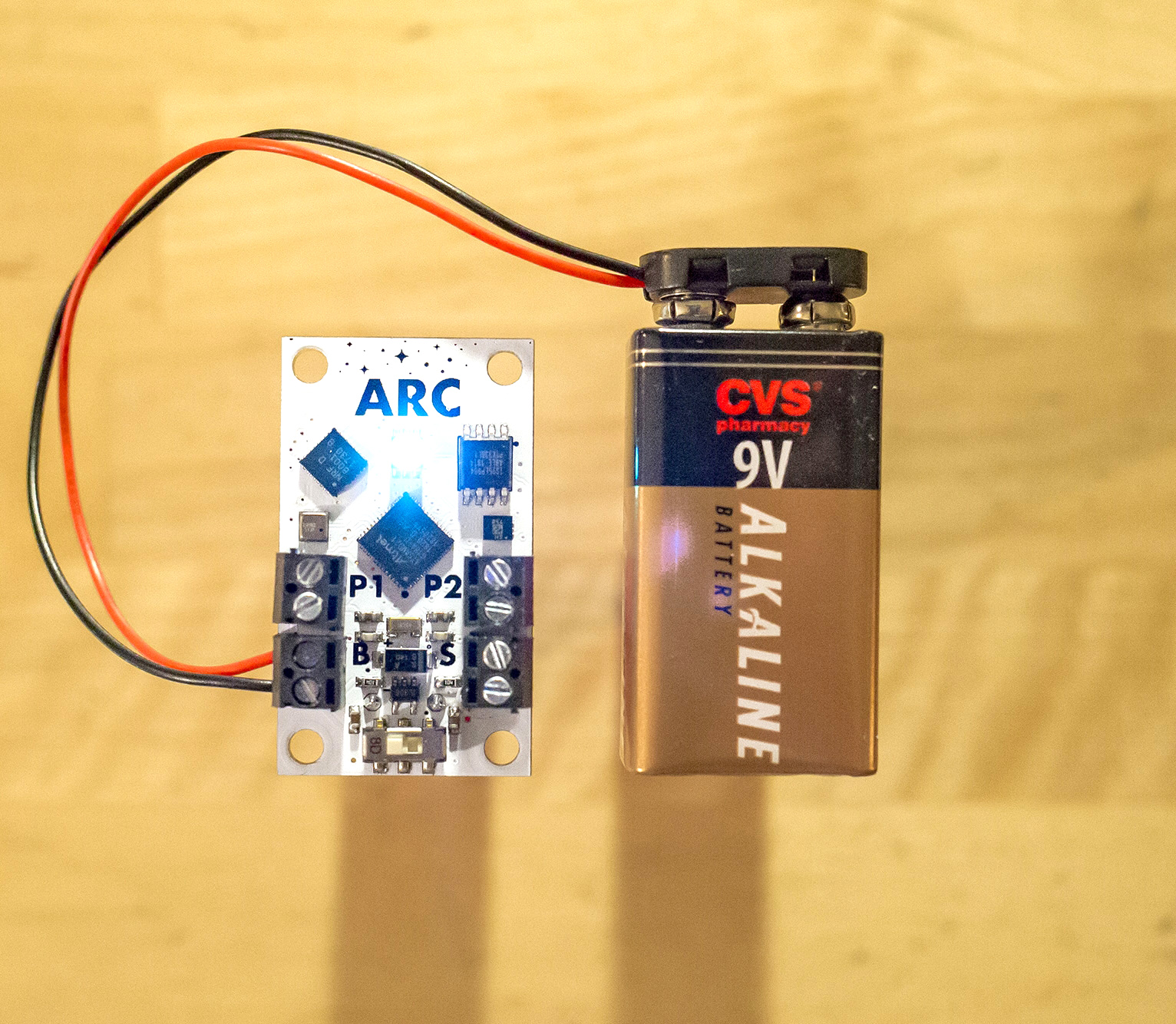

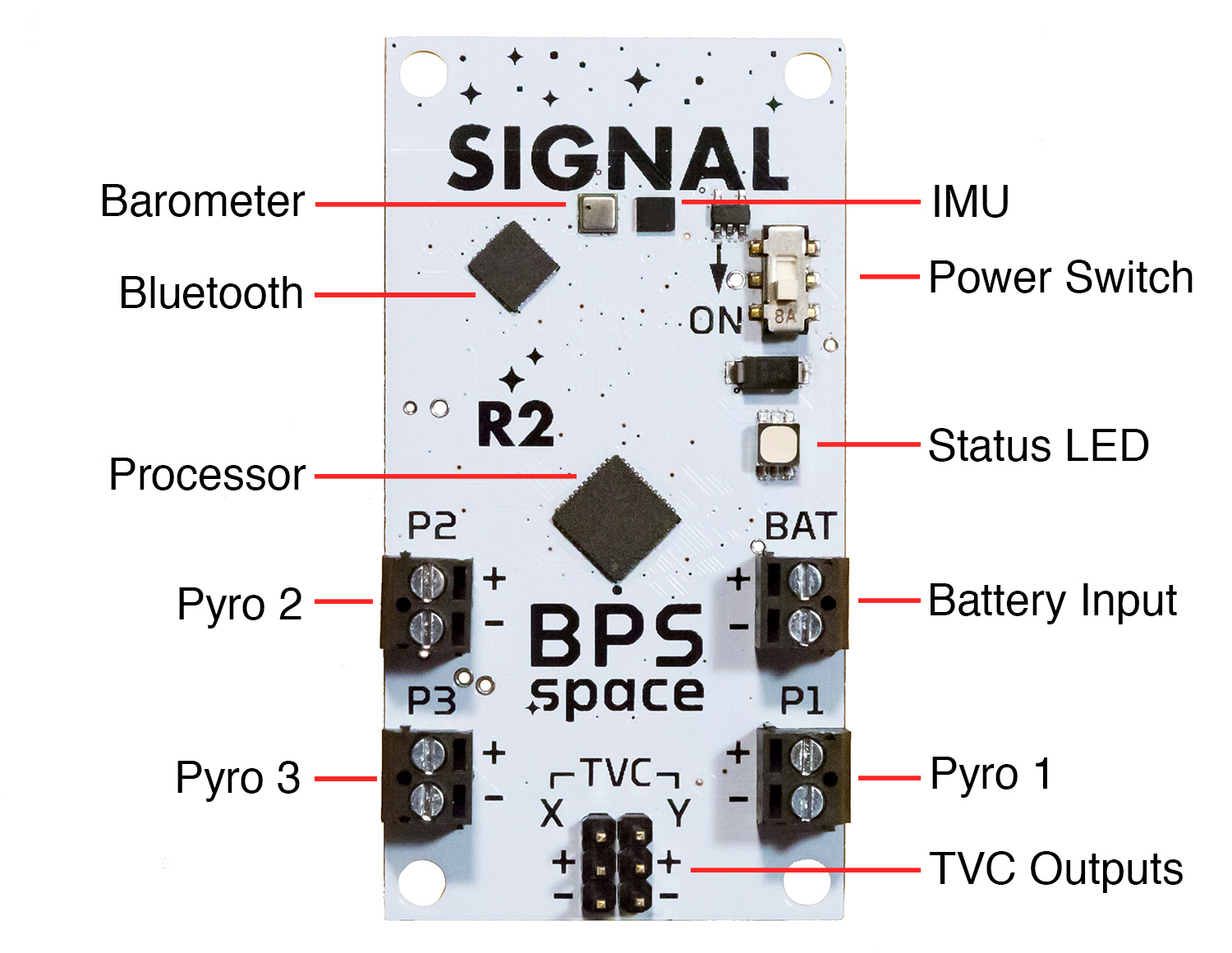

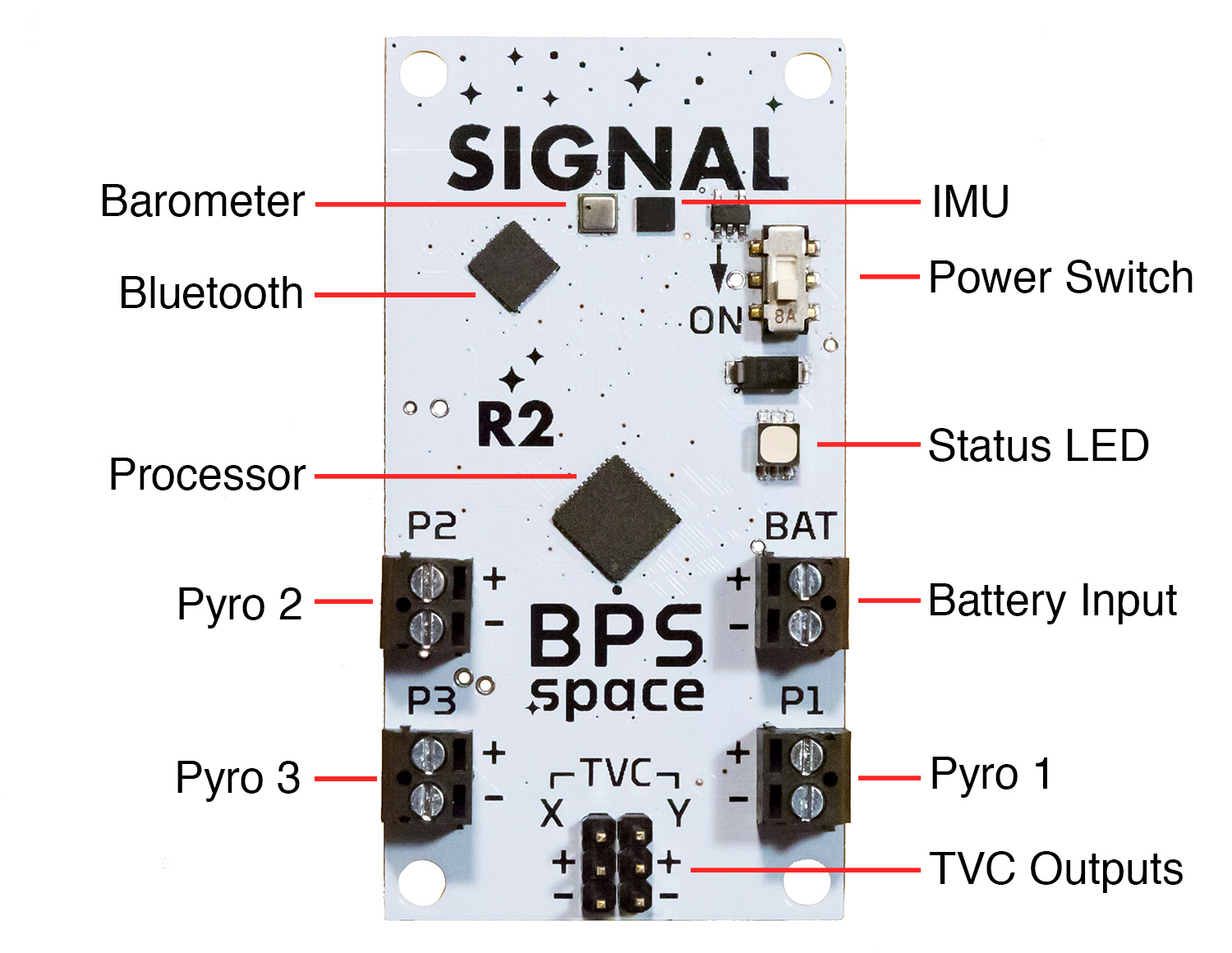

THE COMPUTER

The Signal R2 flight computer runs a high-speed control loop, prioritizing functions depending on the progress of the flight. Thrust vectoring draws considerable current, so once burnout is detected, Signal centers and locks the vectoring mount. Focus is then set on detecting apogee and triggering pyro events. It needs at least 8V; 9V alkalines or 11.1V LiPos recommended.

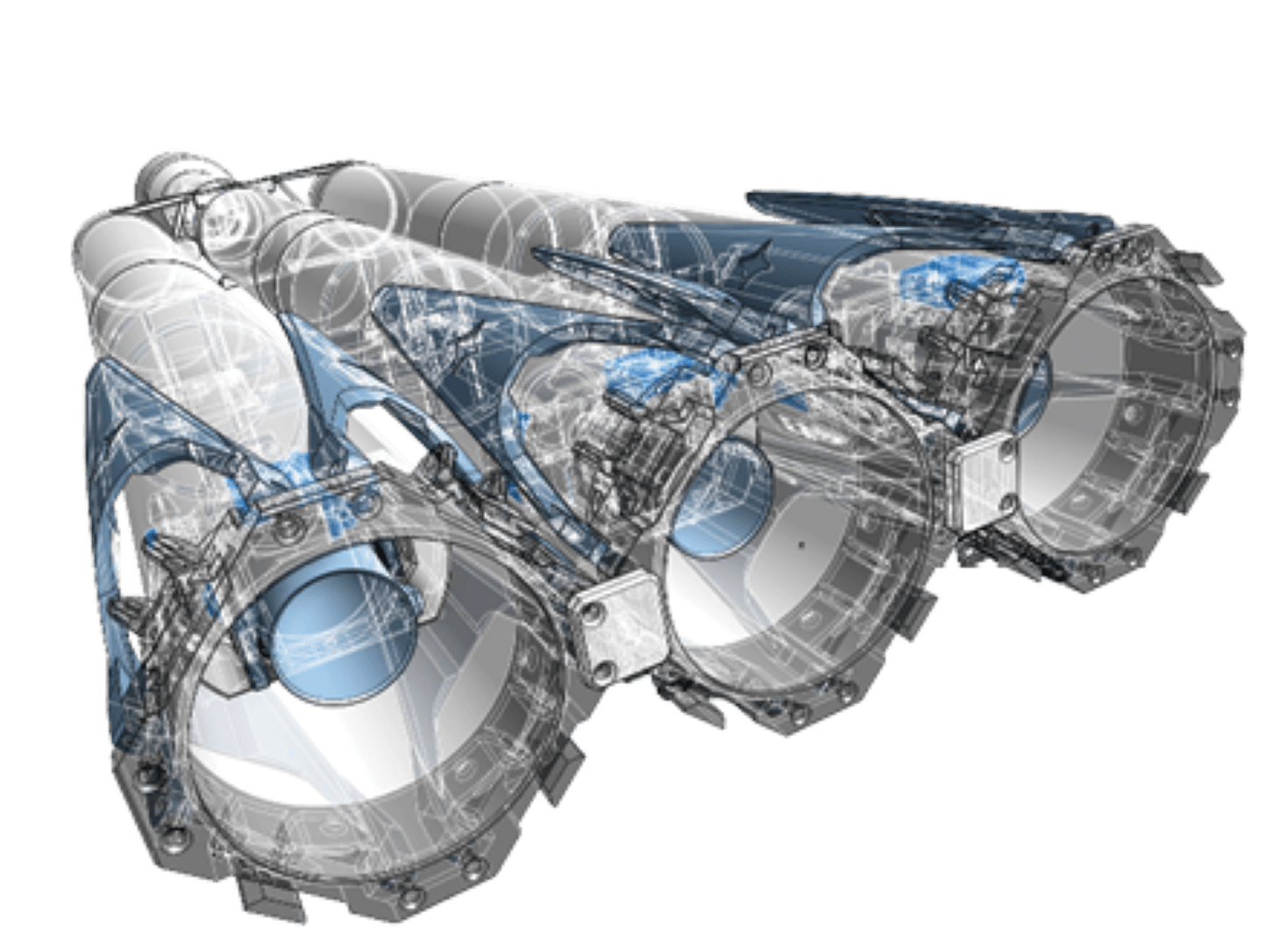

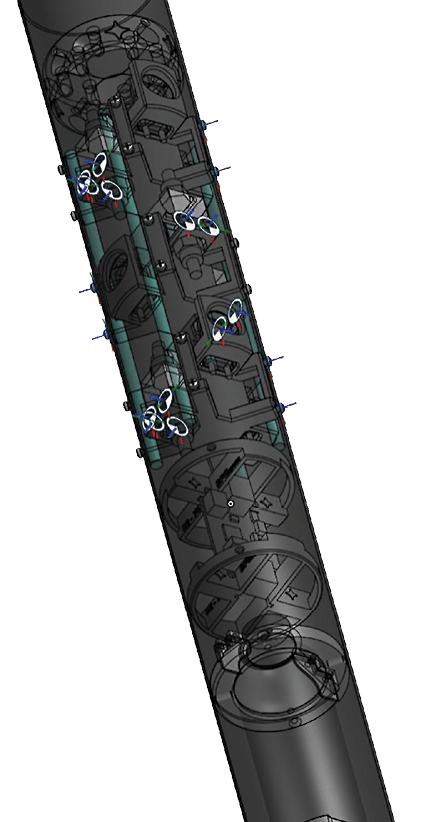

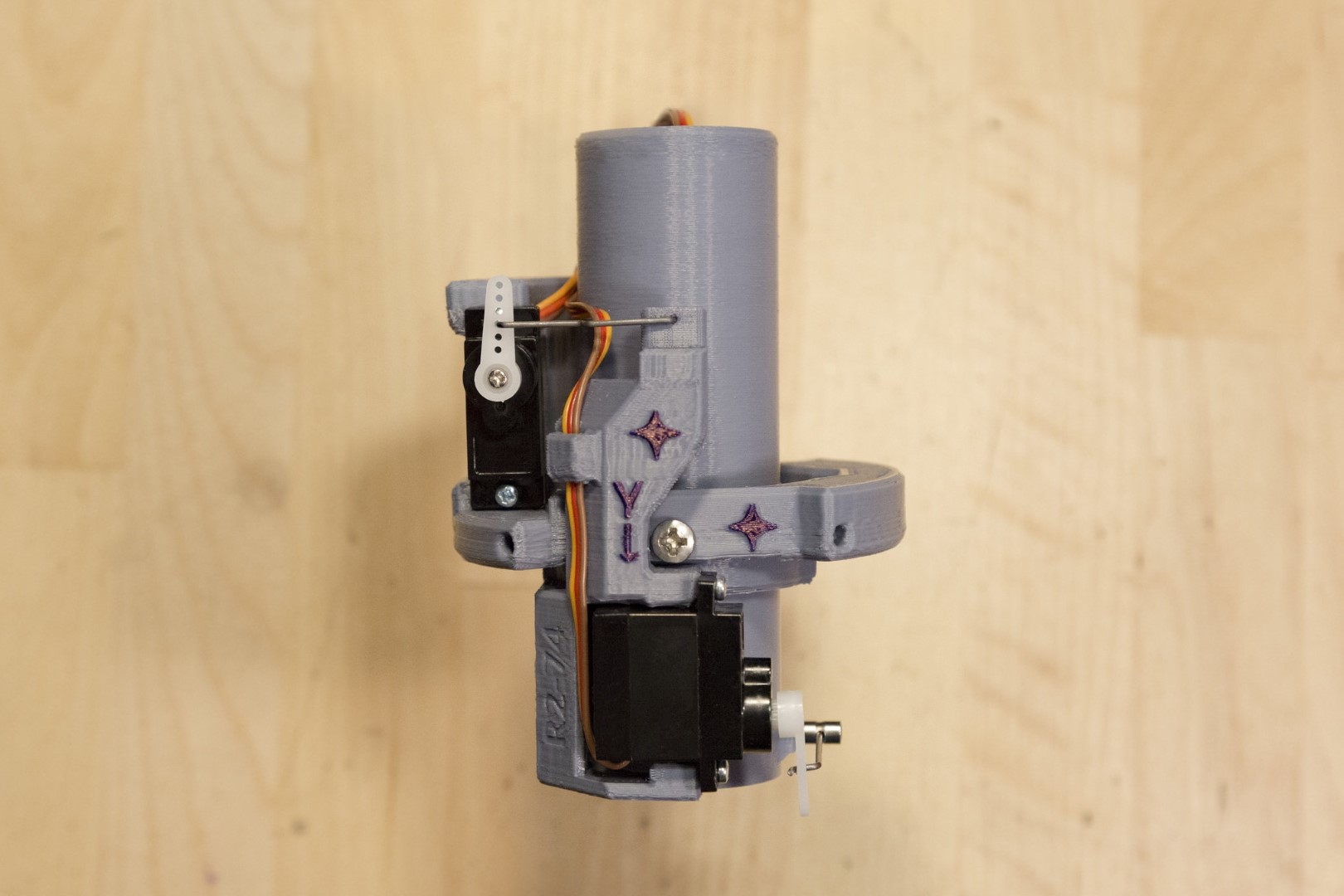

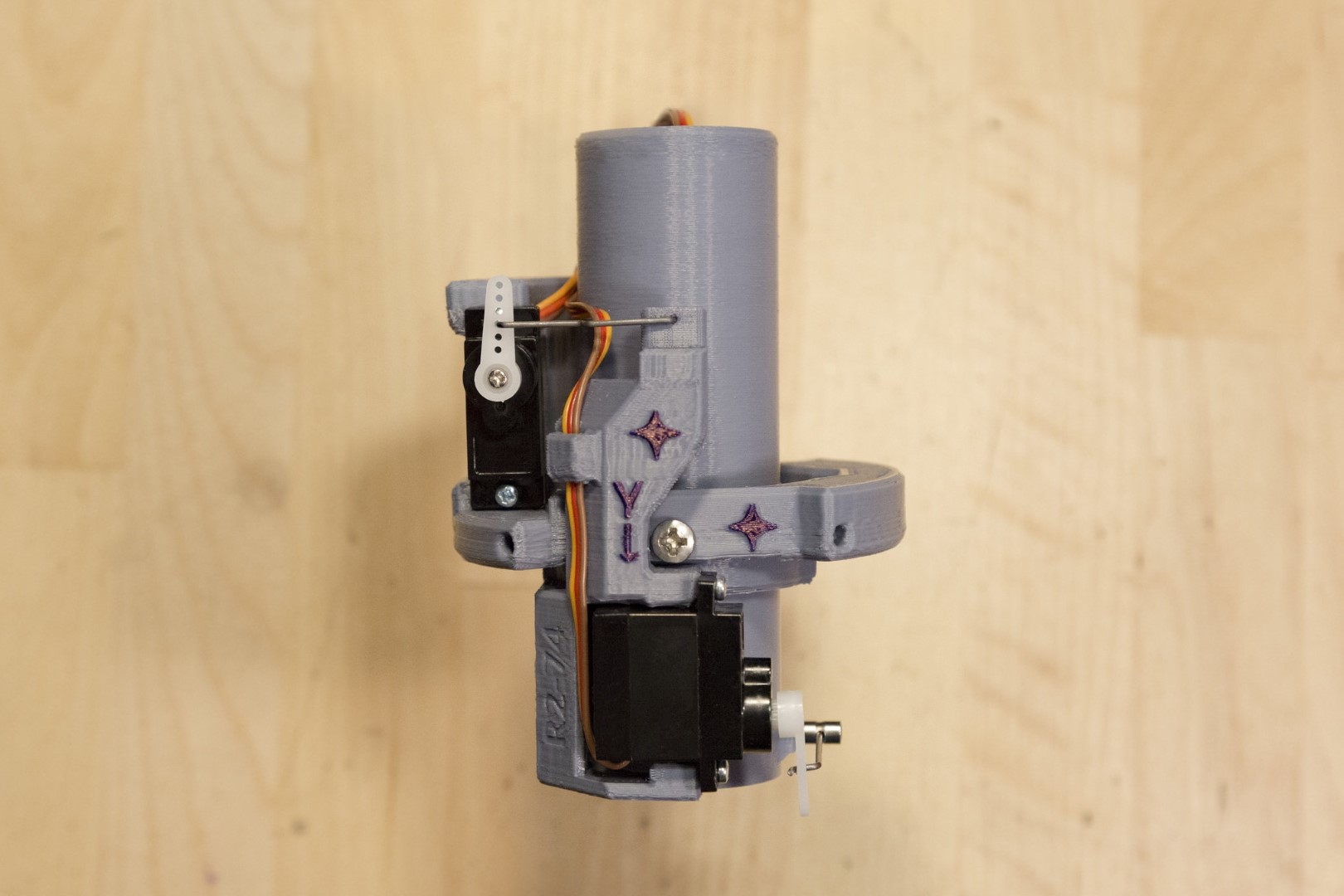

THE TVC MOUNT

Developed over three years of iterative design, the thrust vector control motor mount is made from 3D printed PLA material.

It uses two 9g servos, geared down for higher accuracy. The assembly can gimbal a motor ±5 degrees on each axis, X and Y. Though the mount will work with up to 40N of force, it works best with lower impulse motors, especially those with long burn times.

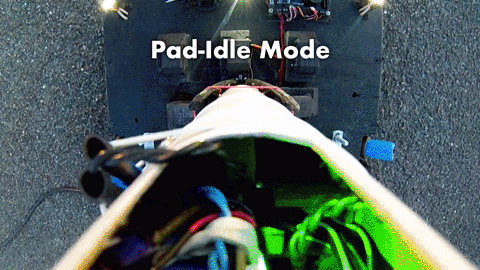

THE SOFTWARE

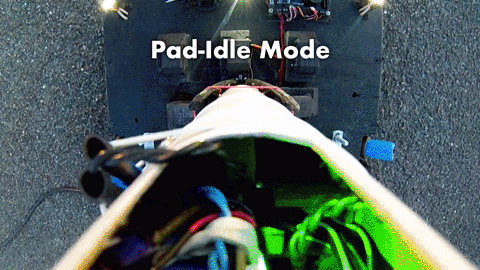

The flight software tracks vehicle flight dynamics while the rocket is powered on. Signal looks for cues to shift system states at liftoff, burnout, apogee, and landing. This makes operation simple — once the settings file is configured for flight, just turn on the flight computer and it automatically enters Pad-idle mode. Signal can detect launch in under 10ms. Once detected, thrust vectoring is activated, in-flight abort is armed, and high-frequency data logging begins.

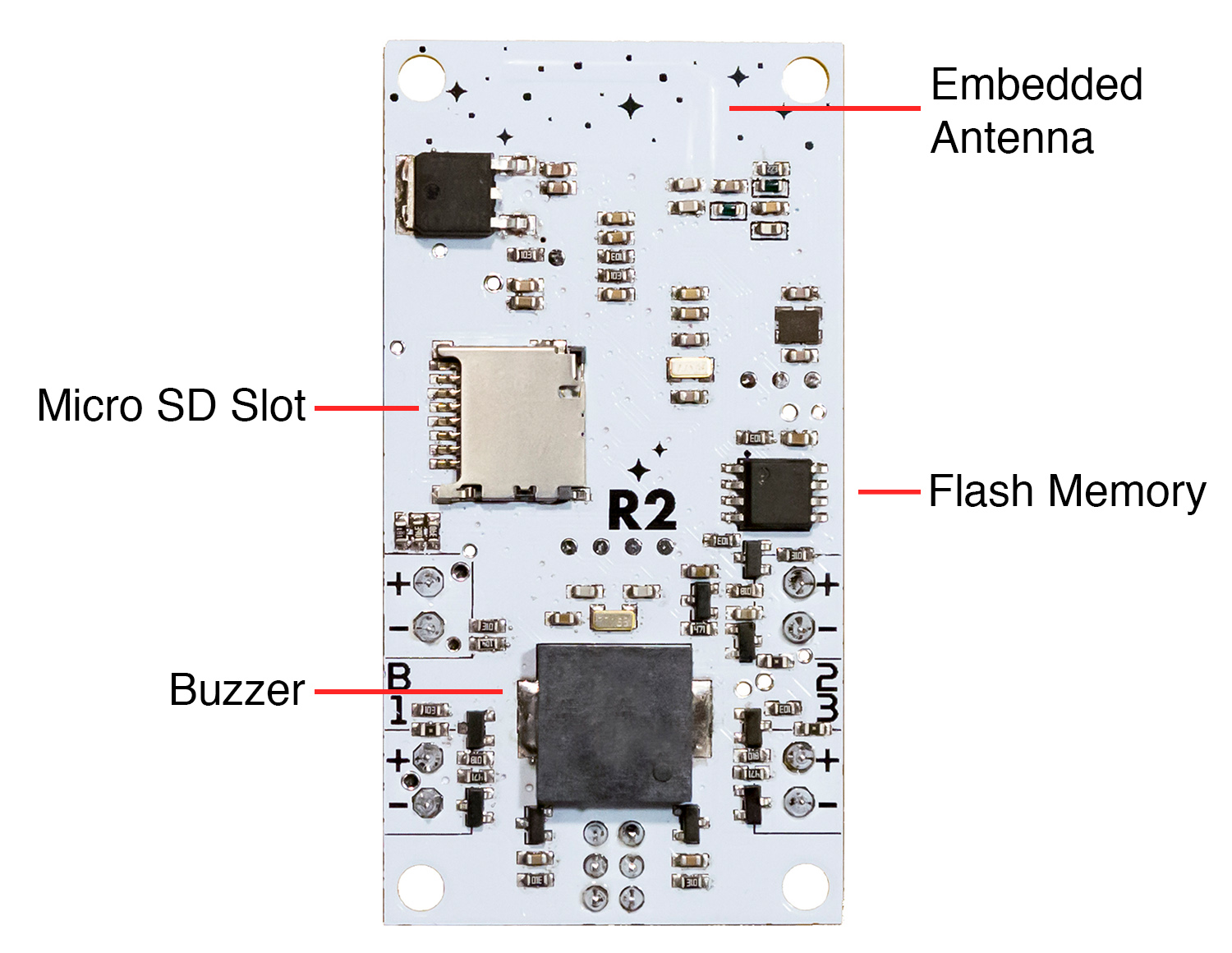

THE DATA

In-flight data logging takes place at 40Hz. Vectoring output, vehicle orientation, altitude, velocity, acceleration, and several other data points are recorded using a custom protocol to a high-speed flash chip. Upon landing detection, Signal creates a new CSV file on the microSD card, dumping flight data into it. Once the data is verified to match, the flash chip is cleared and Signal is ready to fly again. A 1GB card can store hundreds of flights. Flight settings are programmable in a settings file on the card.

THE APP

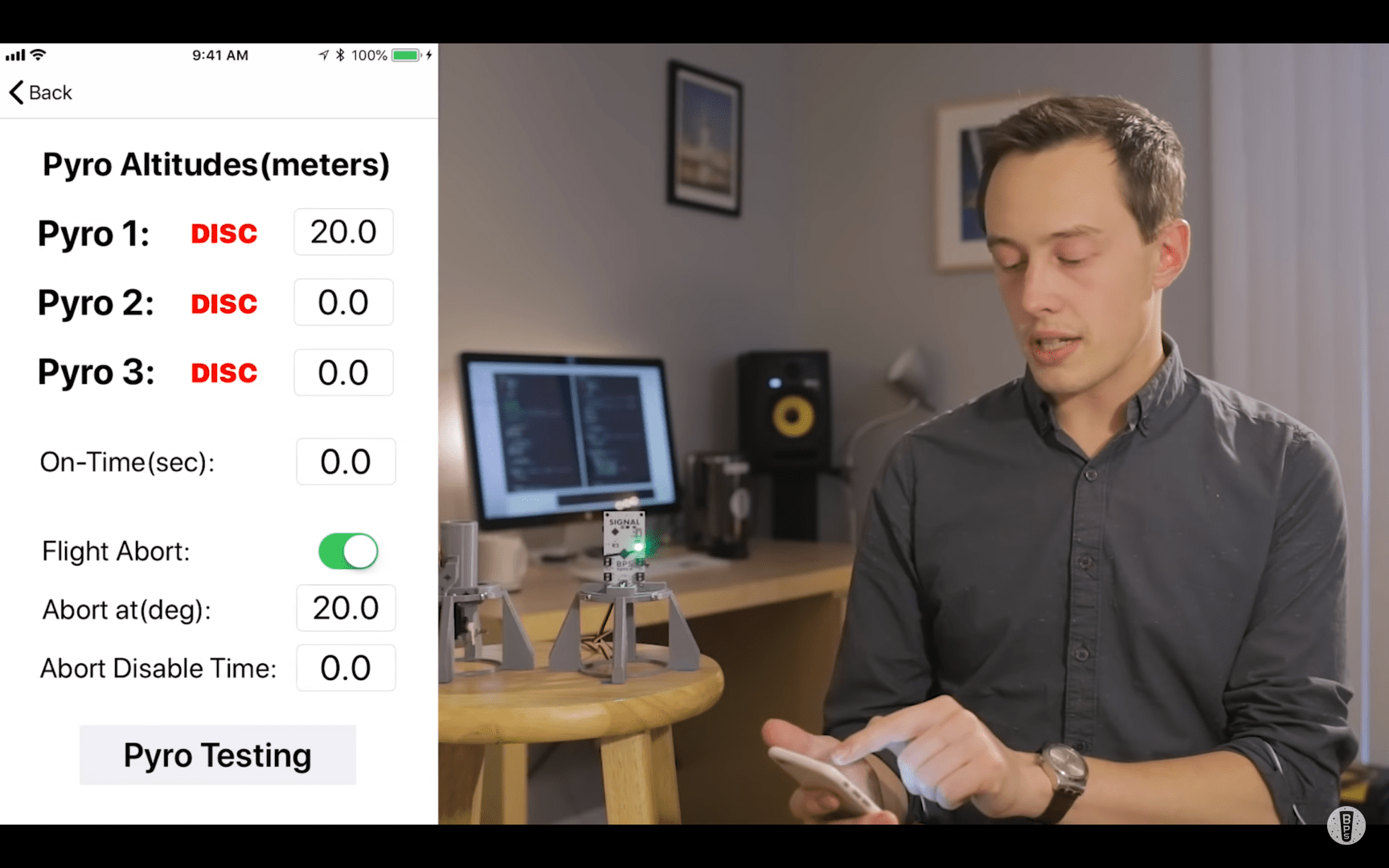

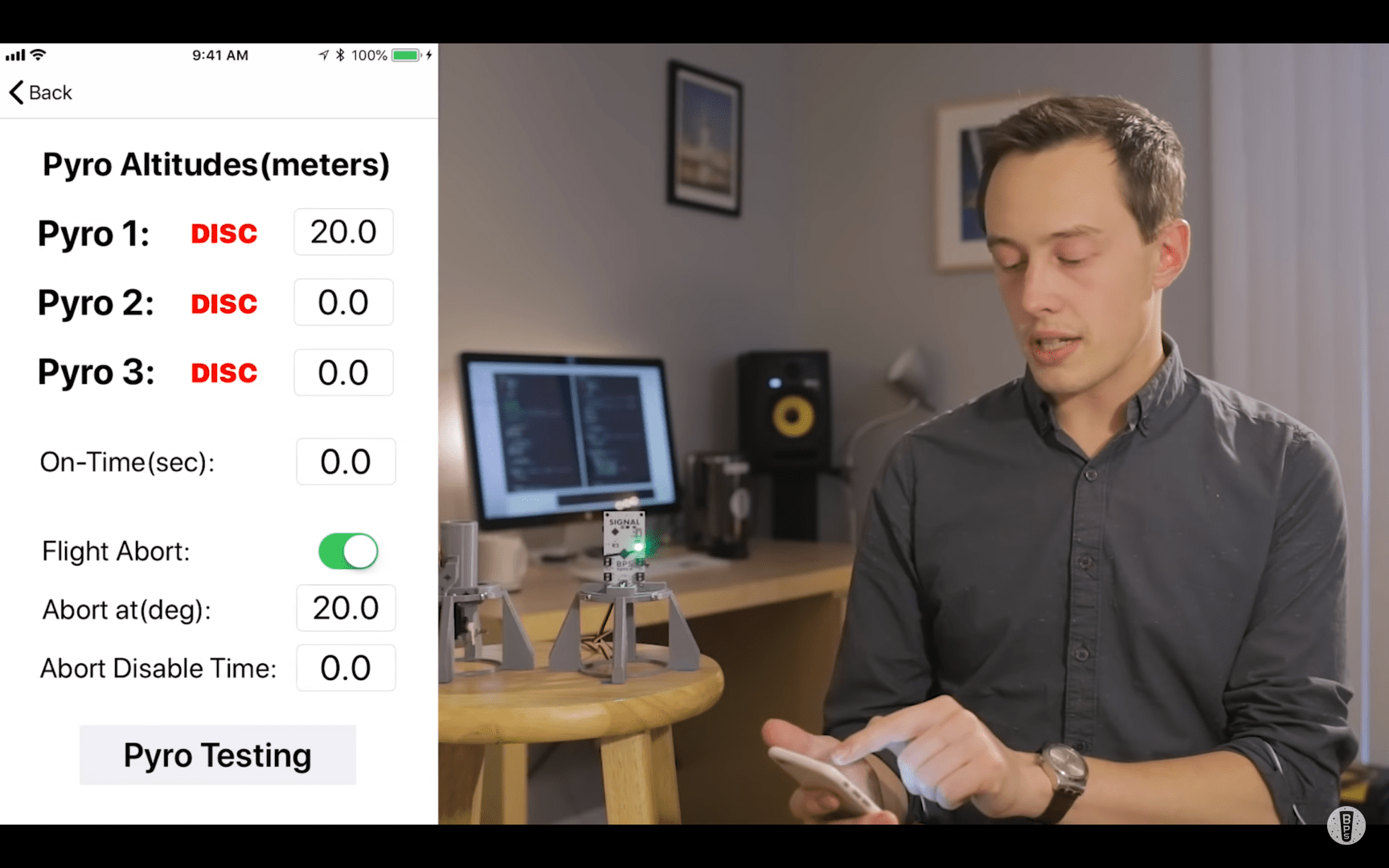

Signal is configured using an app on an iOS or Android smartphone.

The app helps the user configure TVC sensitivity, parachute deployment altitudes, the abort system, ground testing, rocket tuning, and more. My goal is to put Mission Control in your pocket.

Build your own scale model Rocket Lab Electron by following the “Build Signal R2” tutorials at the BPS.space YouTube channel, and try it out!

PROPULSIVE VERTICAL LANDING – Drop It While It’s Hot

When I started building my Signal TVC kits in spring 2017, I put my propulsive landing project on hold. This past year I got back to it: I started drop-testing my experimental Echo rocket from a drone and began a new YouTube series, “Landing Model Rockets.”

The series explains my entire process, from selecting motors, to planning the flight profile, to developing a new control board for propulsive landing. It comes in two flavors: Blip, a DIY version using breakout boards and through-hole components; and Blop, a lighter, surface-mount PCB. Both are based on the powerful MK20DX256VLH7 processor that’s used in the Teensy 3.2 microcontroller, with a Bosch BMP280 barometric pressure sensor and InvenSense MPU-6050 inertial measurement unit (IMU). For now I’m sharing these experimental boards with my Patreon supporters.

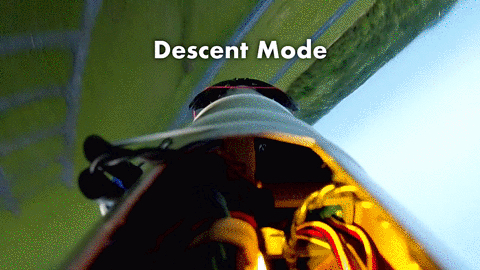

So how can you land with solid rocket motors if you can’t throttle them? It’s all about timing! If the flight profile is fairly well known and the legs are built to withstand small hops and drops, the motor can be fired at just the right time to slow the vehicle down for a soft landing. As the rocket nears the ground, the microcontroller reads the barometric altimeter and fires the retro motor.

Four landing legs deploy by rubber band,

and the rocket lands upright. In theory.

Turns out vertical landing is super hard! As the rocket slows to a near-hover, horizontal drift becomes an issue. I’m already deep in the weeds programming the math necessary to control for this. I’m also experimenting with a tiny LIDAR sensor for really precise rangefinding to the ground.

After several very near misses (watch them on YouTube), I refuse to not stick the landing in 2019! Follow me on Twitter to stay up to date.

ZERO TO ROCKETEER

I started out from scratch in rocketry; I’m all self-taught. After graduating with a degree in audio engineering from Berklee College of Music in 2014, I saw what SpaceX and other aerospace companies were going for with propulsive landing technology and I was hooked. I knew I wanted to get into rocketry to get a job at one of these companies, and I wasn’t in a position to pay for another college degree. I figured instead I could demonstrate what I was teaching myself by propulsively landing a model rocket the same way SpaceX landed the Falcon 9. It was a literal “shower idea.”

I started BPS in 2015 with the goal of achieving vertical takeoff and vertical landing (VTVL) of a scale model Falcon 9 rocket. This would require me to solve two tough problems — thrust-vectored flight and propulsive landings — using solid-fuel hobby rocket motors.

I picked up a few textbooks (I strongly recommend Rocket Propulsion Elements by George Sutton and Structures by J.E. Gordon), found a few good YouTube tutorials for coding and mechanical design, and got to work experimenting.

BPS has produced a lot of rocketry flight computers. Like maybe way too many. Here they are in chronological order.

I naïvely thought it would take four months. My first ten launches were failures. But the eleventh succeeded, and the successes accelerated after that. After four years of hard work, crashes, and iterative designs, I’m now achieving beautiful thrust-vectored launches of several rockets, including my 1:48-scale Falcon Heavy — three cores! — that you can watch on my YouTube channel.

And after some very near misses, I’m confident my Echo rocket will stick the vertical landing in 2019. Rather than attempt to throttle a solid-fuel motor, I’m firing the entire retro motor —also TVC’ed —at the precise time and altitude to enable a soft touchdown. It hasn’t been easy.

KITS FOR MAKERS

Of course this technology is still not mature, and it’s my hope that the advanced model rocketry community will build upon what I’ve done. In 2017, I began selling my Signal flight computer board and TVC motor mount together in a kit. After getting user feedback, the computer was redesigned from the ground up to include Bluetooth — Mission Control from your phone!

BPS.space is now a proper company and a full-time job for me, funded through flight computer sales, the BPS.space Patreon page, YouTube ad revenue, and sponsorships.

This kit is for advanced rocketeers. If you don’t have experience with scratch-built rockets, I recommend you hone your skills first with an Estes ready-to-fly kit and seek advice from fellow rocketeers at the National Association of Rocketry Facebook Group and the Rocketry Subreddit.

And if you’ve got some experience, I hope you’ll give it a try! I’ve even shared a scale model of the Rocket Lab Electron you can build using my tutorials.

THRUST VECTOR CONTROL – Ready to Aim Fire

Model rockets have fins and launch quickly, but real space launch vehicles don’t; they actively aim — vector — their rocket exhaust to steer the rocket. With thrust vectoring, your model rockets can slowly ascend and build speed like the real thing, instead of leaving your sight in seconds.

THE COMPUTER

The Signal R2 flight computer runs a high-speed control loop, prioritizing functions depending on the progress of the flight. Thrust vectoring draws considerable current, so once burnout is detected, Signal centers and locks the vectoring mount. Focus is then set on detecting apogee and triggering pyro events. It needs at least 8V; 9V alkalines or 11.1V LiPos recommended.

THE TVC MOUNT

Developed over three years of iterative design, the thrust vector control motor mount is made from 3D printed PLA material.

It uses two 9g servos, geared down for higher accuracy. The assembly can gimbal a motor ±5 degrees on each axis, X and Y. Though the mount will work with up to 40N of force, it works best with lower impulse motors, especially those with long burn times.

THE SOFTWARE

The flight software tracks vehicle flight dynamics while the rocket is powered on. Signal looks for cues to shift system states at liftoff, burnout, apogee, and landing. This makes operation simple — once the settings file is configured for flight, just turn on the flight computer and it automatically enters Pad-idle mode. Signal can detect launch in under 10ms. Once detected, thrust vectoring is activated, in-flight abort is armed, and high-frequency data logging begins.

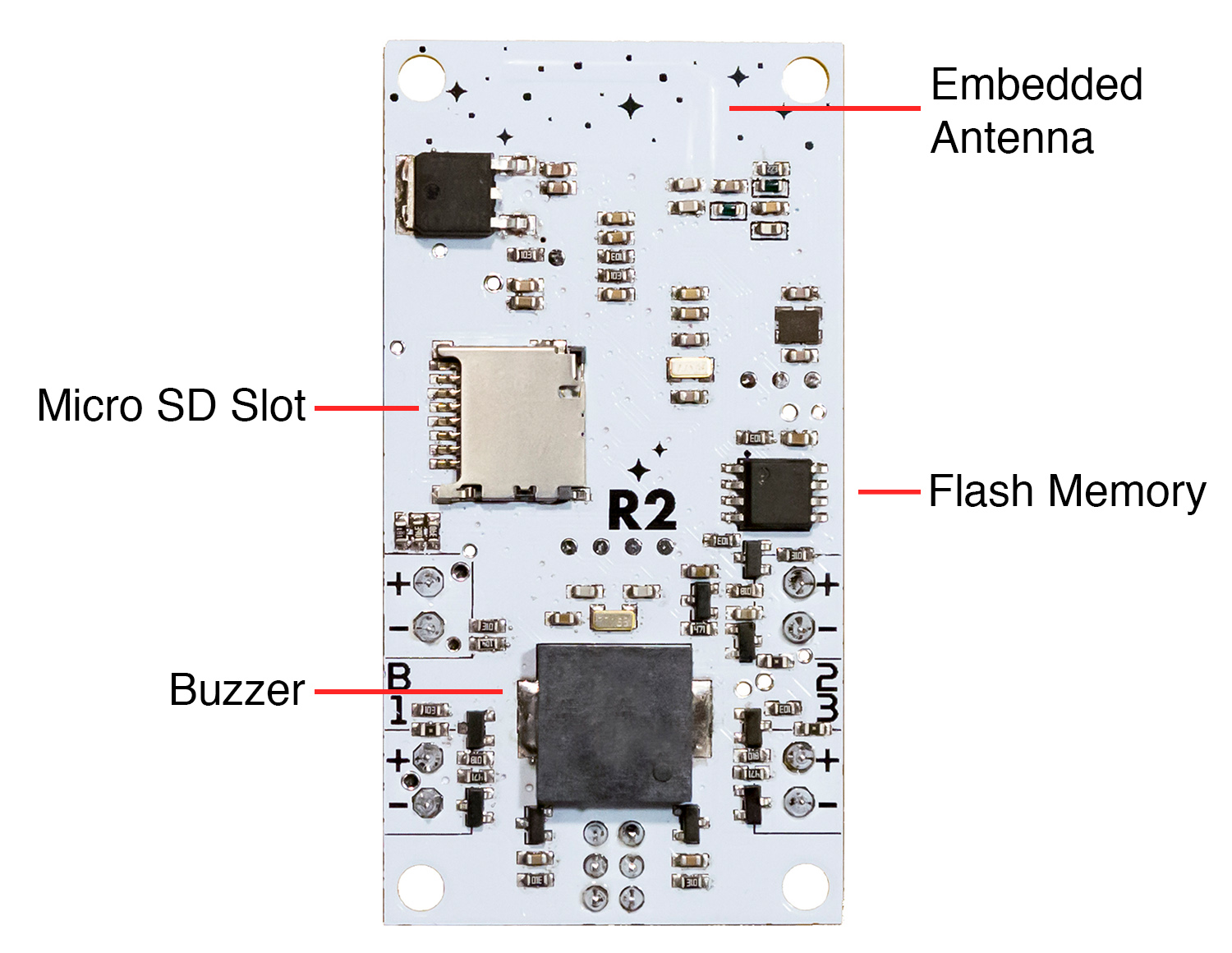

THE DATA

In-flight data logging takes place at 40Hz. Vectoring output, vehicle orientation, altitude, velocity, acceleration, and several other data points are recorded using a custom protocol to a high-speed flash chip. Upon landing detection, Signal creates a new CSV file on the microSD card, dumping flight data into it. Once the data is verified to match, the flash chip is cleared and Signal is ready to fly again. A 1GB card can store hundreds of flights. Flight settings are programmable in a settings file on the card.

THE APP

Signal is configured using an app on an iOS or Android smartphone.

The app helps the user configure TVC sensitivity, parachute deployment altitudes, the abort system, ground testing, rocket tuning, and more. My goal is to put Mission Control in your pocket.

Build your own scale model Rocket Lab Electron by following the “Build Signal R2” tutorials at the BPS.space YouTube channel, and try it out!

PROPULSIVE VERTICAL LANDING – Drop It While It’s Hot

When I started building my Signal TVC kits in spring 2017, I put my propulsive landing project on hold. This past year I got back to it: I started drop-testing my experimental Echo rocket from a drone and began a new YouTube series, “Landing Model Rockets.”

The series explains my entire process, from selecting motors, to planning the flight profile, to developing a new control board for propulsive landing. It comes in two flavors: Blip, a DIY version using breakout boards and through-hole components; and Blop, a lighter, surface-mount PCB. Both are based on the powerful MK20DX256VLH7 processor that’s used in the Teensy 3.2 microcontroller, with a Bosch BMP280 barometric pressure sensor and InvenSense MPU-6050 inertial measurement unit (IMU). For now I’m sharing these experimental boards with my Patreon supporters.

So how can you land with solid rocket motors if you can’t throttle them? It’s all about timing! If the flight profile is fairly well known and the legs are built to withstand small hops and drops, the motor can be fired at just the right time to slow the vehicle down for a soft landing. As the rocket nears the ground, the microcontroller reads the barometric altimeter and fires the retro motor.

Four landing legs deploy by rubber band,

and the rocket lands upright. In theory.

Turns out vertical landing is super hard! As the rocket slows to a near-hover, horizontal drift becomes an issue. I’m already deep in the weeds programming the math necessary to control for this. I’m also experimenting with a tiny LIDAR sensor for really precise rangefinding to the ground.

After several very near misses (watch them on YouTube), I refuse to not stick the landing in 2019! Follow me on Twitter to stay up to date.