BLACKEAGLE

SENIOR MEMBER

Tunisia’s ISIS problem explained

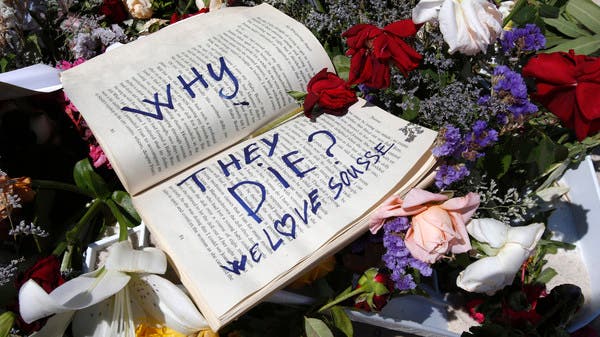

A message laid on flowers at the scene of the Sousse beach massacre (AP)

By Asma Ajroudi | Al Arabiya News

Tuesday, 14 July 2015

Thirty-eight holidaymakers and staff were gunned down last month at a Tunisian resort in a country that has always prided for its “golden beaches, sunny weather and affordable luxuries.”

In March, 22 people, mostly foreigners, were massacred when two gunmen stormed the prestigious Bardo National Museum in the capital Tunis.

Tunisia’s budding democracy - the only one to emerge from the Arab Spring uprisings - is now facing its toughest test.

In addition to an ailing economy and soaring unemployment rate, the tiny North African country has been grappling with the rise of ultra-conservative Islamist groups - some of them violent - since the ouster of the autocratic regime of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali.

The country has also become one of the world’s most fertile breeding grounds for radicals joining the likes of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Nusra Front.

‘Source of Manpower’

Last week, U.N. experts estimated that up to 5,500 Tunisians were currently fighting alongside militants abroad.

An estimated 4,000 Tunisians were in Syria, between 1,000 and 1,500 in Libya, 200 in Iraq, 60 in Mali and 50 in Yemen, reported AFP quoting Elzbieta Karska, current head of a U.N. working group on the use of mercenaries.

Approximately 625 who have returned from Iraq are being prosecuted, the expert said.

Read Also: From beaches to dunes, the shifting sands of Tunisia’s tourism industry.

The recent estimate showed a sharp increase from an earlier 2014 Washington Post report that implied the country was the top exporter of foreign fighters.

“These figures reveal that Tunisia, compared to many other countries, is still a source of manpower for these radical groups,” political analyst Noureddine Mbarki told Al Arabiya News.

What these figures also mean is that these radical groups’ “project” is still “appealing” to young Tunisians, said Mbarki.

In April, the Tunisian interior ministry revealed that up to 12,500 would-be militants were prevented from leaving Tunisian territory to travel to combat zones - another striking figure.

“The question is, what do you do with that [would-be militant] when you catch him? How do you protect him from trying to travel again? And how do you protect yourself from him?” said Mbarki.

“It’s all part of the counter-terrorism campaign,” he said, noting that many of those who were banned from traveling were under surveillance.

‘Root’

But “foreign jihad” (holy war abroad) is not a completely foreign concept for Tunisians.

Tens of Tunisian “holy warriors” were documented to have fought in Afghanistan in the 1980s and 1990s, and during the civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in Iraq following the U.S.-led invasion.

Some of those who returned home attempted to link up with al-Qaeda in the Maghrib (AQIM) and start military camps in the country. Others ended up in jail only to be freed in a presidential pardon after the revolution.

An example would be former al-Qaeda fighter Seifallah Ben Hassine, aka “Abu Iyad al Tounsi”, who in 2011 founded Ansar al-Shariah, the group responsible for the assassination of two high-profile leftist politicians

“The pardons that immediately followed the revolution included such groups. Those who are used to killing and bombing were given the right to become ordinary citizens,” said Mbarki.

Former interim president Moncef al-Marzouki has come under harsh criticism for freeing up to 18,000 prisoners while in office.

‘Domestic policy’

Secularism was strongly imposed under Ben Ali to a point that religious garments, such as the hijab, were strictly banned in the Muslim country.

Some analysts say Ben Ali’s two decades of dictatorial rule might have helped in creating an underground militant Salafist movement that is no longer scared to impose itself onto Tunisia’s political reality.

“Tunisian youths were deprived of expressing their beliefs and ideas, and of performing their religious rights,” Dr. Abu Yareb al-Marzouki, a Tunisian philosopher and expert on Salafist movements, previously told Al Arabiya News.

“Troika gave them space to be function freely. It allowed them to interact with citizens. It allowed them preach,” said Mbarki, in reference to the political alliance that ruled Tunisia through its transitional period.

But Troika and Marzouki often defended themselves by arguing that everyone had an equal right to freedom of expression and political representation and integration.

But the government’s “don’t see, don’t tell” policy with the activities of such groups despite media and intelligence reports urging for surveillance and control, allowed them to smuggle weapons through the Libya border, pointed Mbarki.

“Of course, we are going to be where we are today,” said Mbarki.

Borders

A part of Tunisia’s problem has also been geographical. Sharing a border with Libya and Algeria has posed a series of challenges for the tourist destination.

The al-Qaeda in the Maghrib splinter group Okba Ibn Nafaa brigade, based in Mount Chaambi on the Algerian border, has been using the same tactics that AQIM used against the Algerian army in the Kabylie mountains. The group is also believed to have acquired weapons from Algeria.

The group is responsible for the killing and disfiguring 14 Tunisian soldiers in an ambush in 2014.

So it should probably come as no surprise that Seifeddine Rezgui, the individual behind the Sousse beach resort attack, had trained at a camp in Libya either.

Libya has been plagued with civil war since the toppling of former Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi in 2011.

With two rival governments and armed forces battling for control, the security vacuum allowed radical groups to establish a foothold in the oil-rich country.

So dangerous has the situation become in Libya, that the U.S. is now considering the use of drones in the country to combat ISIS and its radical affiliates, reported The Washington Post.

“I don’t see a difference between people smugglers and terrorist recruitment cells. They both make business of the lives of Tunisian youth,” said Mbarki.

Libya has also turned into a people’s smugglers haven.

Last Update: Tuesday, 14 July 2015 KSA 22:35 - GMT 19:35

https://english.alarabiya.net/en/perspective/2015/07/14/Tunisia-s-ISIS-problem-explained-.html

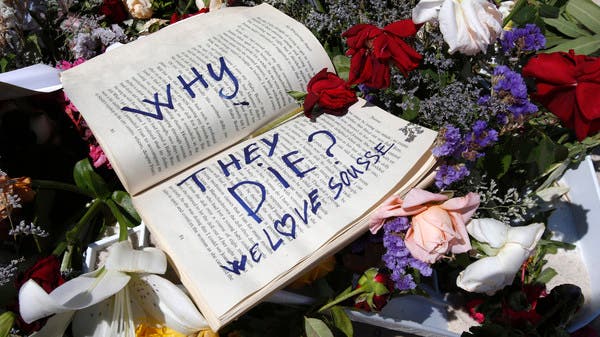

A message laid on flowers at the scene of the Sousse beach massacre (AP)

By Asma Ajroudi | Al Arabiya News

Tuesday, 14 July 2015

Thirty-eight holidaymakers and staff were gunned down last month at a Tunisian resort in a country that has always prided for its “golden beaches, sunny weather and affordable luxuries.”

In March, 22 people, mostly foreigners, were massacred when two gunmen stormed the prestigious Bardo National Museum in the capital Tunis.

Tunisia’s budding democracy - the only one to emerge from the Arab Spring uprisings - is now facing its toughest test.

In addition to an ailing economy and soaring unemployment rate, the tiny North African country has been grappling with the rise of ultra-conservative Islamist groups - some of them violent - since the ouster of the autocratic regime of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali.

The country has also become one of the world’s most fertile breeding grounds for radicals joining the likes of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Nusra Front.

‘Source of Manpower’

Last week, U.N. experts estimated that up to 5,500 Tunisians were currently fighting alongside militants abroad.

An estimated 4,000 Tunisians were in Syria, between 1,000 and 1,500 in Libya, 200 in Iraq, 60 in Mali and 50 in Yemen, reported AFP quoting Elzbieta Karska, current head of a U.N. working group on the use of mercenaries.

Approximately 625 who have returned from Iraq are being prosecuted, the expert said.

Read Also: From beaches to dunes, the shifting sands of Tunisia’s tourism industry.

The recent estimate showed a sharp increase from an earlier 2014 Washington Post report that implied the country was the top exporter of foreign fighters.

“These figures reveal that Tunisia, compared to many other countries, is still a source of manpower for these radical groups,” political analyst Noureddine Mbarki told Al Arabiya News.

What these figures also mean is that these radical groups’ “project” is still “appealing” to young Tunisians, said Mbarki.

In April, the Tunisian interior ministry revealed that up to 12,500 would-be militants were prevented from leaving Tunisian territory to travel to combat zones - another striking figure.

“The question is, what do you do with that [would-be militant] when you catch him? How do you protect him from trying to travel again? And how do you protect yourself from him?” said Mbarki.

“It’s all part of the counter-terrorism campaign,” he said, noting that many of those who were banned from traveling were under surveillance.

‘Root’

But “foreign jihad” (holy war abroad) is not a completely foreign concept for Tunisians.

Tens of Tunisian “holy warriors” were documented to have fought in Afghanistan in the 1980s and 1990s, and during the civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in Iraq following the U.S.-led invasion.

Some of those who returned home attempted to link up with al-Qaeda in the Maghrib (AQIM) and start military camps in the country. Others ended up in jail only to be freed in a presidential pardon after the revolution.

An example would be former al-Qaeda fighter Seifallah Ben Hassine, aka “Abu Iyad al Tounsi”, who in 2011 founded Ansar al-Shariah, the group responsible for the assassination of two high-profile leftist politicians

“The pardons that immediately followed the revolution included such groups. Those who are used to killing and bombing were given the right to become ordinary citizens,” said Mbarki.

Former interim president Moncef al-Marzouki has come under harsh criticism for freeing up to 18,000 prisoners while in office.

‘Domestic policy’

Secularism was strongly imposed under Ben Ali to a point that religious garments, such as the hijab, were strictly banned in the Muslim country.

Some analysts say Ben Ali’s two decades of dictatorial rule might have helped in creating an underground militant Salafist movement that is no longer scared to impose itself onto Tunisia’s political reality.

“Tunisian youths were deprived of expressing their beliefs and ideas, and of performing their religious rights,” Dr. Abu Yareb al-Marzouki, a Tunisian philosopher and expert on Salafist movements, previously told Al Arabiya News.

“Troika gave them space to be function freely. It allowed them to interact with citizens. It allowed them preach,” said Mbarki, in reference to the political alliance that ruled Tunisia through its transitional period.

But Troika and Marzouki often defended themselves by arguing that everyone had an equal right to freedom of expression and political representation and integration.

But the government’s “don’t see, don’t tell” policy with the activities of such groups despite media and intelligence reports urging for surveillance and control, allowed them to smuggle weapons through the Libya border, pointed Mbarki.

“Of course, we are going to be where we are today,” said Mbarki.

Borders

A part of Tunisia’s problem has also been geographical. Sharing a border with Libya and Algeria has posed a series of challenges for the tourist destination.

The al-Qaeda in the Maghrib splinter group Okba Ibn Nafaa brigade, based in Mount Chaambi on the Algerian border, has been using the same tactics that AQIM used against the Algerian army in the Kabylie mountains. The group is also believed to have acquired weapons from Algeria.

The group is responsible for the killing and disfiguring 14 Tunisian soldiers in an ambush in 2014.

So it should probably come as no surprise that Seifeddine Rezgui, the individual behind the Sousse beach resort attack, had trained at a camp in Libya either.

Libya has been plagued with civil war since the toppling of former Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi in 2011.

With two rival governments and armed forces battling for control, the security vacuum allowed radical groups to establish a foothold in the oil-rich country.

So dangerous has the situation become in Libya, that the U.S. is now considering the use of drones in the country to combat ISIS and its radical affiliates, reported The Washington Post.

“I don’t see a difference between people smugglers and terrorist recruitment cells. They both make business of the lives of Tunisian youth,” said Mbarki.

Libya has also turned into a people’s smugglers haven.

Last Update: Tuesday, 14 July 2015 KSA 22:35 - GMT 19:35

https://english.alarabiya.net/en/perspective/2015/07/14/Tunisia-s-ISIS-problem-explained-.html