Hi folks! Just thought I would get into the Submarine side of things. I have written an article recently for the Naval Association of Canada (NAC) Canadian Military magazine called "Starshell" and offer it for your reading and comments bearing in mind that this paper is only my own opinion. Cheers!

Does Canada Need a Submarine Fleet?

(NAVAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA-STARSHELL MAGAZINE)-SUMMER 2019 ISSUE

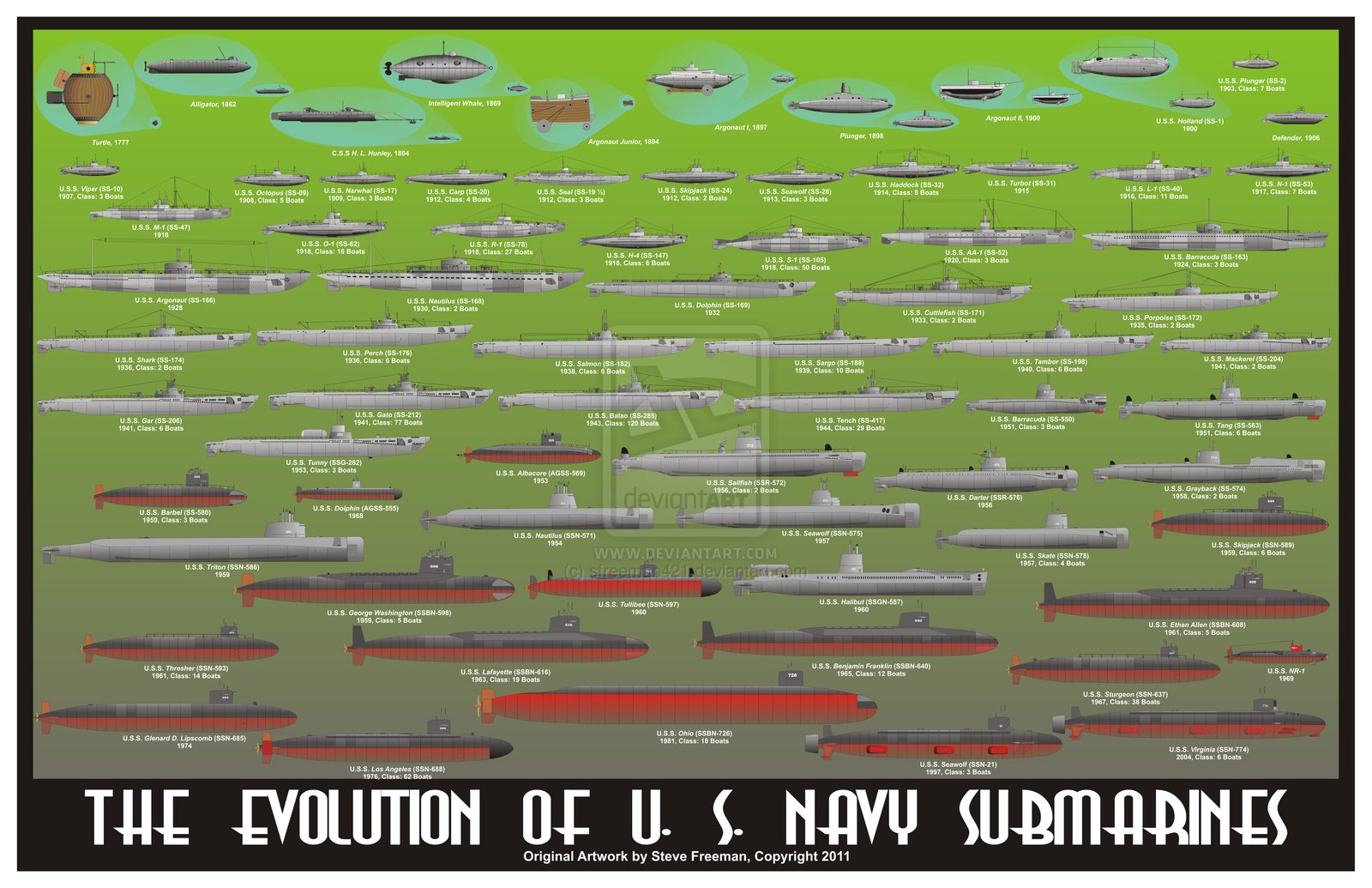

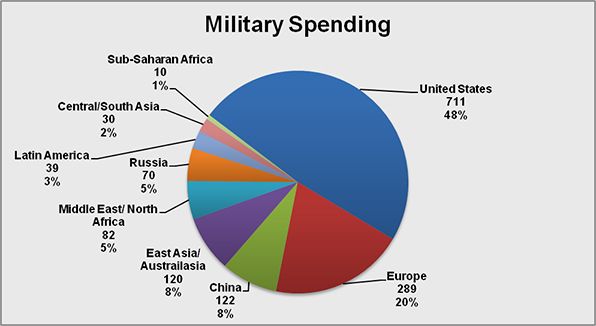

After the end of the Cold War many states cut the funding to their militaries – the so-called ‘peace dividend.’ But now that the brief moment seems to be over, many states are recapitalizing their militaries, their navies in particular. Not only are states building surface ships to renew their fleets, they are also building sub-surface capabilities. Canadian allies from Australia to the United States, and non-allied competitor states Russia and China, are focusing on submarine development. Like other NATO states, Canada cut the defence budget in the 1990s, what military supporters refer to as ‘the decade of darkness.’ Given the renewed focus on submarine capability among Canada’s allies and potential adversaries, what is Canada doing about submarines? There are three questions that need to be addressed on this topic:

•

Does Canada need submarines?

•

Does Canada need new submarines?

•

If so, what type of submarine and capabilities would Canada need?

This arcticle will examine these three questions.

Does Canada Need Submarines?

Yes it does. There are several reasons why Canada needs submarines. Canada is a maritime state – it has oceans on three of four of its borders, and a significant proportion of its trade travel via the oceans. The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) supports government priorities and economic prosperity and contributes to the safety, accessibility and security of Canadian waters.1 The CCG does a superb job at enforcing Canadian fisheries laws and undertaking maritime search and rescue, and boating safety. As well, the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) and the RCMP do a great job of enforcing Canadian law within the maritime borders of the country. However CCG ships, and the law enforcement agencies have no real means to defend Canada or its maritime sovereignty claims, especially in the Arctic.

These are arguments why Canada needs a navy, but why does it need submarines? Although the United States is Canada’s most important trading partner, the Canadian economy nonetheless relies heavily on goods being shipped by sea across the world. This means Canada has a stake in protecting shipping from potential threats. This can be done by a surface fleet, but sub-surface capability is also a very important part of the mix. The best way to give other submarine-possessing states pause is, without question, another submarine.

More than 40 countries have submarine capabilities. And the number of submarines being built and operated increases every year. While Canada probably does not need to worry about submarines possessed by say Singapore, there are countries which possess submarines about which Canada should be concerned – Russia and China are the most likely states to be of concern within this modern submarine sea-power paradigm.

Take the case of the recent buildup of Russia’s Arctic naval presence. Russia has been updating its navy and been increasingly active in the north. This has been called the biggest military push since the fall of the Soviet Union.2 A small Russian push here, a slightly larger one there, and suddenly the RCN will sail into ostensibly Canadian waters at its own peril. Canada does not have the military forces to defend every square centimeter of its sovereign claims on any of its three oceans, including the Arctic. But, as a state, Canada must make an effort to deter action against it. Both Russia and China have enormous submarine resources and are constantly adding to their fleets almost annually with most of their more modern submarines being much quieter and harder to locate. For example, Russia’s Nuclear/Conventional Submarine fleet includes 70 attack submarines including the new Akula class Attack SSNs, Yasen class guided missile SSGNs and the Typhoon and Barei class ballistic missile SSBNs, making Russia second only to the USA in submarine strength in the world. (http//russianships.info/eng/today, 2018). China is also no slouch when it comes to their submarine fleet. They have at least 63 Nuclear/Conventional submarines including their modern Jin class SSBNs, Shang I, II and III class Attack SSNs and up to 48 Air-Independent Propulsion (AIP) SSK conventional subs (The National Interest-China’s Advanced Submarines Are Breaking Records, July 26 2018). To say that both countries are escalating their numbers of submarine forces on an unprecedented scale, is an understatement and has given western allies great concern recently. This is another reason why Canada needs submarines to counter this potential threat.

The mere fact that other states are rapidly building up their submarine capabilities, means that Canada should have its own subs as well. First, the best way to keep other submarines out of Canadian waters is for Canada to have its own submarine capability. As former head of the Canadian navy, Admiral Paul Maddison, said in testimony before a Senate committee, “The best counter to a submarine is a submarine. In terms of our surveillance of our ocean approaches and the protection of our own sovereignty, I consider submarine capability to be critical.”3 If Canada wants to know who and what is in its waters, Admiral Maddison said, “a modern submarine capability is crucial.”4

As discussed in the government’s new defence policy document Strong, Secure, Engaged, the roles of the Canadian Armed Forces, including submarine interests, are divided into three categories: defence of Canada and North America; support of Canadian expeditionary deployments to joint action ashore and support of Canada’s interests in global maritime stability.5 The North Atlantic and the Arctic Ocean in particular are concerns for Canada. Recent Russian submarine fleet excursions into these areas, plus increased activities in the air and at sea, have given NATO great concern about the security of the Atlantic Areas Of Responsibility (AORs). NATO is establishing a new Joint Force Command and sees Canada as a major player. This is the second reason why Canada needs to have submarines – to fulfill allies’ expectations and to carry Canada’s share of the defence burden.

A third, reason to have submarines is to assist in training Canadian, NATO and other allied naval personnel in the art of Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) and Special Forces Operations. One of the Canadian Navy’s main roles during the Cold War was ASW, and this capability may be needed more than ever in the future as more countries acquire submarines. This operational expertise is not built overnight. It needs to be developed via sustained training and practice. In the past, Canada’s diesel-electric submarines have provided excellent platforms with which to train in ASW with allied navies. Canadian submarines have played the cat and mouse exercises, something that is extremely useful for training purposes for surface, air and sub-surface assets.

Fourth, if Canada hopes to sit at the table when operations involving submarines are discussed, then Canada must have a modern and credible submarine capability. An important element in possessing any submarine is the concept of Water Space Management (WSM) and the ‘Prevention of Mutual Interference’ (PMI). These systems can be thought of as akin to an under-water traffic control system that monitors (‘de-conflicts’) the movements of submarines. This ensures that submarines do not accidently collide or fire upon allied submarines. The concept was adopted by NATO in the early days of the Cold War, and is used by national, NATO and allied submarine operating authorities (SUBOPAUTHs) to ensure the safety of submarine operations in the world’s oceans. Using a number of different protocols and procedures, submarines are routed to their operating areas using a SUBNOTE which provides a ‘Moving Haven’ (MH) of defined dimensions (including depth) in which the submarine must remain while transiting.6 If a country doesn’t have submarines, it doesn’t participate in WSM and isn’t privy to information about other states’ operations in its waters. Without submarines, Canada would not know whose submarines are in its waters.

This is particularly acute in the Arctic. It is a foregone conclusion that there are submarines beneath Canada’s polar ice cap, and they are not Canadian. This will become more important as global warming allows increased exploration of the Arctic seabed, and its rich resources. Only systems that can reach under the ice can tell us who else is operating there. Canada can be judged sovereign, in the context of alliance and collective defence, only if it can contribute to its own national security. The final reason for why Canada needs submarines is the ability to add stealth to naval operations. Submarines are the ultimate stealth platforms, able to operate in areas where sea and air control are not assured, and gain access to areas denied by other forces. Each submarine-possessing state, including Canada, understands that modern submarines, with their superior combat power and freedom of action, are fundamental components possessing a level of strategic power that confers an influence out of proportion to initial investment beyond their size. These are multi-mission platforms, fitted with specialized suites of equipment, weapons and stealth characteristics that enable them to operate covertly. The mere possibility that one might be loitering near strategic bases can confine a fleet or restrict its movements, interrupting seaborne commerce that sustains states in peace and in conflict.

Suffice to say that a country with the largest coastline in the world, depending heavily on seagoing commerce, with regular maritime challenges, from fishing boats lost at sea to ‘Turbot Wars,’ and a Russian build up of Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic naval forces, need an adequate and modern submarine fleet. As long as Canada needs a navy, it will need submarines. When testifying before a Senate committee, Admiral Paul Maddison stated that “For a G8 [now G7] nation, a NATO country like Canada, a country that continues to lead internationally and aspires to lead even more, I would consider that [loss of submarine capability] to be a critical loss of a fundamental capability and a very difficult one to regenerate at a future date..”7

Does Canada Need New Submarines?

Canada currently has four Victoria-class (SSKs) diesel-electric submarines – HMCS Victoria, Windsor, Corner Brook and Chicoutimi. These boats were purchased from Britain in the 1990s and after a slow start, they are now very useful and usable assets. One of the four submarines is always in a three-year extended deep maintenance period; the remaining three submarines are conducting operations or are in maintenance periods in accordance with the fleet operating plan. The submarines were extremely active in 2018, participating in a number of exercises in the Pacific, the Mediterranean and the North Atlantic. Since becoming operational, the Victoria-class submarines have not only been involved in recent exercises in both the Atlantic and Pacific but also in other classified surveillance operations we are not, and will not be privy to.

Despite being active, the submarines are now over 28 years old since being commissioned by the UK in 1990. HMCS Victoria was originally scheduled for retirement five years from now. The other three submarines would have followed soon after. They have been regularly updated and maintained but they cannot last forever. Eventually, it will cost too much to maintain them, and there will be increasing safety issues.

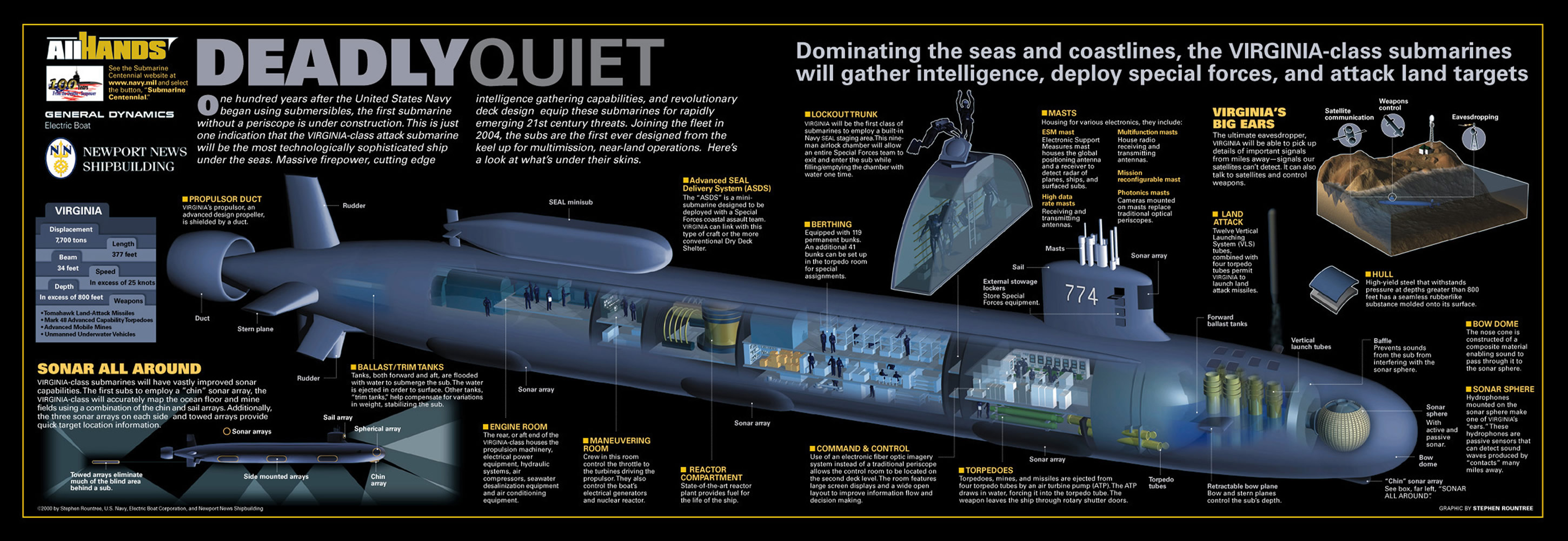

It would be considered a dire day if Canada were to lose the ability to know what is happening under the sea in the three ocean approaches of the country. The procurement process is a long one. Submarines can take up to twenty years from design to actual entry into service. Physical construction time depends on man hours available, and capability of the yards building them. In the US, the Virginia class SSN for example, took two ship yards almost 2 years to build it, but the follow on ships are being built in about a year. Once christened, they are still not commissioned. They have to run through an extensive acceptance program run by the US Navy, which can take up to a year or longer by itself. The Germans on the other hand, have built boats in ten years from concept. China bought ‘new’ Kilo class submarines from the Russians and got them in a year… So the short answer is, it depends on which country is building what. Diesel vs. AIP vs. Nuclear and how much redundant safety is built in. The US builds in the most safety and redundancy of any manufacturer in the world.

Canada’s defence policy adopted in 2017 – Strong, Secure, Engaged – reiterates the need for Canada’s navy to be comprised of a balanced fleet of platforms. This would naturally include submarines.8 In this policy, the government has clearly acknowledged the unique qualities and options a modern submarine capability brings to the table, and the pressing need to maintain this capability.

What Submarine Capabilities Would Canada Need?

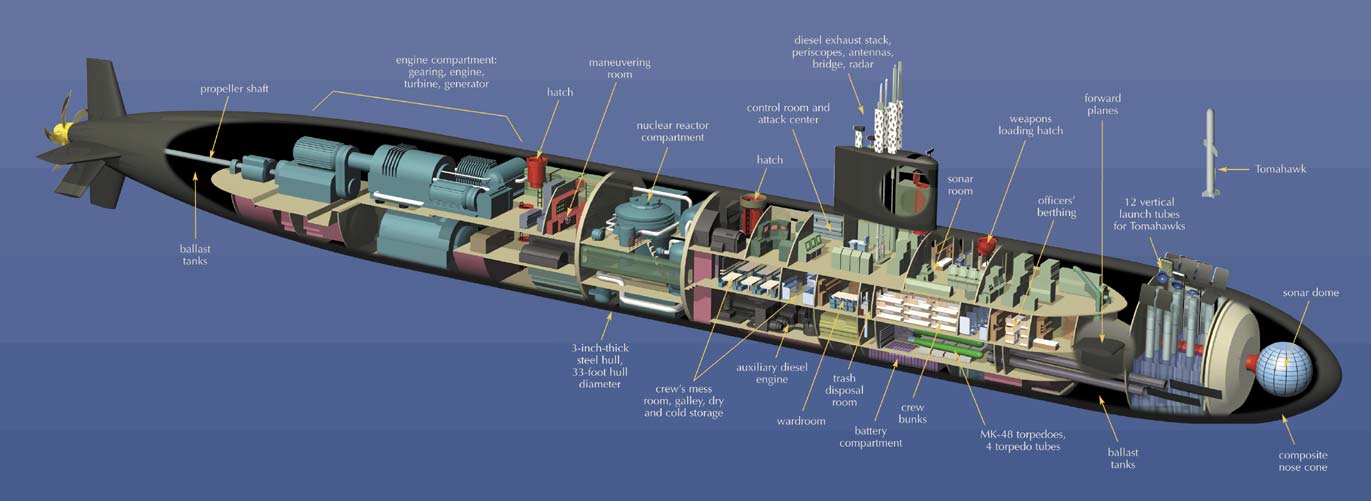

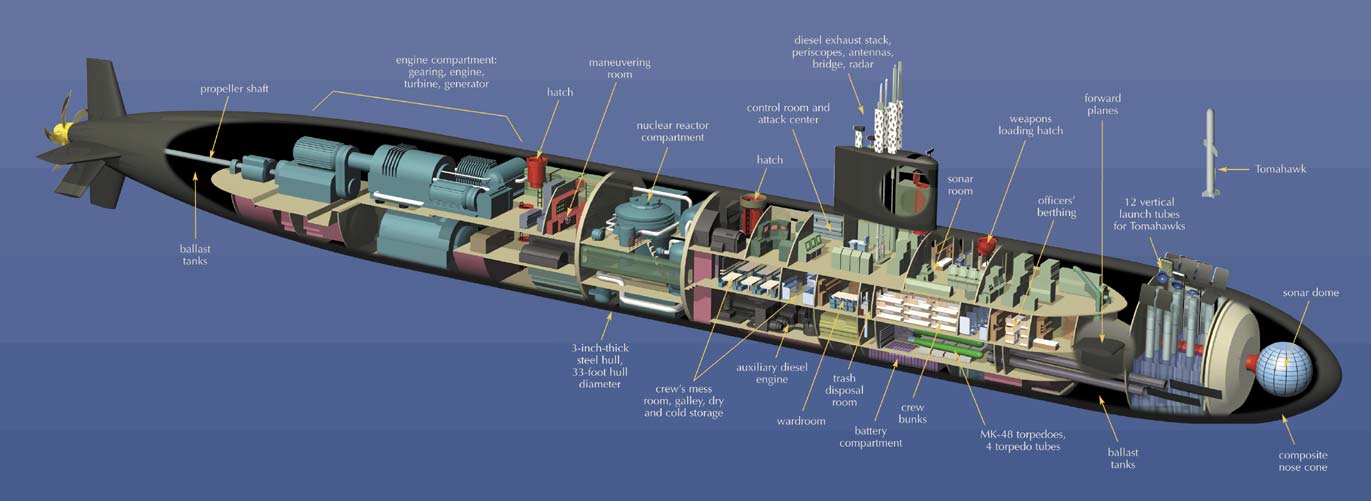

A modern submarine fleet designed to meet Canadian requirements must have the ability to operate in all three oceans. This requires blunt discussions with Canadians about propulsion systems for a modern submarine that must operate in the world’s most hostile and unforgiving maritime environments. The Victoria-class submarines do not possess a significant under-ice capability, making them ineffective at best in Canada’s Arctic. It would be optimal if new Canadian submarines are able to operate in the Arctic without restriction and have a vigorous under-ice capability, with long endurance (including crew habitability considerations). Given the extent of Canada’s coastlines, and the nature of the waters around the country, Canadian submarines need to operate for prolonged periods, at great distances, with unlimited endurance in some of the most unforgiving waters on the planet. Canada will need to take care before selecting a modern submarine design.

There is currently only one type of AIP system that can regenerate the atmosphere necessary for prolonged submerged operations in the Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic Oceans – that is nuclear propulsion. Only nuclear submarines (SSNs) can stay under ice and generate their own oxygen without the need to surface. As well, they have the power to surface even through several feet of ice. Nuclear-propelled subs have merit and should at least be in the conversation as replacements for the Victoria-class SSKs. The British Astute-class, the American Virginia-class, and the new French Barracuda Suffern-class (which replaces the French Rubis class, the first of which entered service in 2017) SSNs, are all world-class boats that Canada may want to consider for its new submarine fleet. These boats would greatly enhance Canada’s sea power, would be game changers to Canadian capability, and give other states pause before entering Canadian waters, although they would all need adaptation to Canadian operational requirements.

Canadian submarines require an ocean-going capability that can patrol far off the coasts of Canada, with prolonged forays into the Arctic, withstand repeated surfacing through several feet of ice, and deploy worldwide either independently, or as part of a Canadian or coalition task force. Flexibility for future equipment changes and habitability requirements must be considered in any Canadian design. These requirements would lead to a modern ocean-going conventionally-powered AIP submarine with a displacement of at least 5000+ tons (submerged) as is the case with the new French Barracuda Suffern class SSNs (

French - Wikipedia Barracuda class submarine) with re-enforced hulls and conning towers for breaking through the heavy ice fields of the Arctic. The issue with size is tied directly to power generation and submerged endurance. The bigger and more capable the submarine, the more power generation is required to operate efficiently.

Different forms of non-nuclear AIP, all of which need additional types of fuel,9 have been developed by, and for, European states with very different submarine operating areas than Canada. These systems are usually hybrid systems with diesel engines as the primary power generation source for endurance and an AIP system for limited periods of stealth operation.10 Notably, with the exception of both the Japanese Soryu-class and the Shortfin Barracuda Block 1A class being built for Australia, their AIP SSKs are all much smaller (2500 tons or less) and closer to resupply sources than Canadian submarines conducting domestic operations would be. Moreover, these systems are not powerful enough to generate and clear the atmosphere of the submarine, should there be emergency ‘incidents’ on board such as fires which would require immediate surfacing to clear smoke. Therefore, at their current level of technology, these subs are unsuitable for prolonged high Arctic under-ice operations. Other non-allied countries are either buying German Type 212/216 modern AIP SSKs, with Russian aligned countries acquiring older Russian Kilo Class SSKs or considering the new Russian Saint Petersburg or Lada class AIP SSKs. It is note-worthy that all of these classes are approximately 2500 tons or less and not suitable for open ocean or Arctic operations.

A modern Canadian conventional submarine would need a continued refinement of diesel generation technology, greater power and fuel efficiency, accompanied by better battery technology, such as lithium. This would allow increased energy storage capacity, and the potential for augmentation of an AIP source for unlimited submerged power generation (For a discussion of this, see Canadian Forces College-LCdr Simon Summers, JCSP 44-Air Independent Propulsion: An Enabler For Canadian Submarine Under-Ice Operations-2017-2018).

But does the submarine that Canada needs exist? The answer is not yet, but it could in the near future. Is a modern Canadian conventional AIP submarine fleet a viable option? Yes. However, an AIP propulsion system that can provide power endurance comparable to a nuclear power plant has yet to be developed. This is not to say it cannot be done, just that it has not yet been done. It will take more research and developmental technology, with commensurate investments in infrastructure and training, before larger ocean going modern AIP SSKs can favourably compare to the prolonged under-ice operations of SSNs that have been developed by the USA, United Kingdom, Russia or China. These larger nuclear powered submarines (at least 8000 to over 20000 tons) all have the endurance and size to operate in the high arctic with no restrictions when surfacing through heavy ice. In short, Canada needs to develop technology that will mirror nuclear propulsion, but not be nuclear.

If Canada is serious about new submarines that are capable of operating in all three oceans, it must look to Canadian industry for a solution, and push for acceptable alternatives to fossil fuels that will cause a technological revolution in power and battery technology. To operate in the high Arctic means that there are significant challenges to overcome so that Canadian submarines can achieve more than seasonal ice edge forays. Canadian industry will be a necessary catalyst to push the types of AIP technologies that must be considered in future Canadian submarine replacements.

The USN, United Kingdom, Russian and Chinese Nuclear submarines all have the capability to not only go under the high arctic ice-fields, but to surface where-ever and when-ever they desire. Present Non-nuclear AIP battery technology is not yet sophisticated enough to allow for this nuclear alternative capability. Other non-nuclear countries have not developed this R & D technology as they do not have to operate in Canada’s harsh environments. Canada needs nuclear-like modern AIP capabilities for operations under the ice. The technology however, need not be developed from scratch. Canada can learn from other countries that are in the process of developing/building new submarines – France, Japan and Australia in particular. Australia is pushing extant technology to produce a modern conventional submarine, supported by a unique AIP system. This is certainly unconventional in approach, but could this be the solution for Canada? Only time will tell. It is important for Canada to pay close attention to the Australian experience, as many of its submarine requirements mirror those of Canada. Naval Group, based in France, is producing 12 large 5000+ tons (submerged) non-nuclear AIP-powered versions of its new Suffern-class SSNs called the Short-Fin Barracuda Block 1A for Australia. They will replace Australia’s nine Collins-class SSKs.11 Japan has also designed and produced a 4200+ ton modern AIP Soryu-class submarine that would also be an option to consider for Canada.

The question then becomes: Can Canada build a large non-nuclear modern AIP submarine? The market for submarines has grown exponentially, but there are only a handful of countries capable of building them. There are shipbuilders that are capable of designing and building Canadian submarines, but almost all are European and most have little expertise with larger ocean-going AIP designs that have become the purview of the nuclear-powered submarine community. Is Canada capable of building them? Yes, but the last time Canada built submarines was during the First World War for Britain. However, there is a compelling argument that with the assistance of an experienced submarine shipbuilder, Canada could produce a fleet of modern AIP equipped SSK submarines, with extensive under-ice capabilities.

Once Canada decides on a design, it is reasonable to assume that a built-in-Canada solution, supported by a foreign shipbuilder with submarine-building expertise, would be most likely. Optimally, replacement submarines would be Canadian built, with Canadian steel and Canadian jobs, but with foreign expertise. Submarines are key military assets that take time to build. As well, it takes time to train personnel and develop the facilities and processes for the maintenance of the subs. Whatever submarine may be chosen, it is critical that Canadian support, infrastructure and crew training are included; a vital and expensive component in itself. In addition to building these submarines, the necessary infrastructure, particularly the supply chain, submariners and training must be in place in order to support these submarines throughout their service life from project inception to initial operation.

A submarine replacement project would reap rewards in Canadian technology as well as leverage domestic capabilities arising from the National Shipbuilding Strategy. However, if Canada were to instead procure an ‘off the shelf’ solution, and fail to address unique Canadian environmental requirements, many of these benefits would be lost and the RCN would struggle to maximize their return on any significant investment.12

If Canada decides that it needs new submarines and begins to consider the capabilities, it is also time to consider the number. The current fleet of four Victoria-class submarines is totally inadequate to provide an effective presence in the three oceans on Canada’s borders. A much larger fleet of 5000+ ton modern AIP submarines is required. It would be important for Canada to look towards Australia and their experience for their future submarine capabilities when deciding on submarine fleet size. A 2017 Canadian Senate Defence Committee report recommended 12 modern AIP-equipped SSK submarines, with extensive under-ice capabilities.14 That number is ideal given the need for a balance between a 2% increase of GDP in defence budget, the many increases in recent and future covert and overt mission requirements by the government, Canada’s ability to adequately counter the fast-growing threats from non-allied states around the world and finally, to take on a much stronger role within NATO which has recently been a concern by our allies. This would enable the stationing of six submarines on both the East and West Coasts and provide the option to effectively deploy to the high Arctic. Three boats would be high readiness/deployed world-wide , one to two would be in deep maintenance (every five years) and one to two in build up/build down/training mode.

Conclusion:

There is no doubt that Canada’s submarine capability is in great peril. The current fleet of submarines is near the end of its safe and useful life. There is also no denying current fiscal constraints on defence spending. A credible submarine capability brings with it enhanced flexibility to conduct military operations and the ability to collaborate with other states. The most cursory of glances at a globe illustrates the vastness of Canada’s ocean areas and a future Canadian submarine capability must be able to operate fully in these areas. It must provide future Canadian governments with options from which to respond to international crises. Having a strategic submarine fleet, no matter what propulsion plant is used, will be essential to Canada’s future defence requirements. Canada doesn’t need a large navy, but it does need the navy to be adequate to defend Canadian maritime approaches and to deter challenges to security and sovereignty.

A defence budget increase to at least 2% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), as proposed by the Standing Senate Committee on National Security13 would give Canada the resources needed to fund a future submarine acquisition program. A replacement of the Victoria-class, with a commensurate increase in infrastructure and submariner strength, would not only be possible, but a built-in-Canada design adopted from AIP subs either under construction or development, could be acquired and would be a transformative change for the country.

Building these submarines would mean no negative effects on Canada’s defence needs in the future, or on Canada’s strong economy. The ability to deploy submarine forces at home or abroad from bases in Halifax or Esquimalt, has considerable appeal to a country that wishes to renew its NATO presence. Technologically, there is no reason why a country like Canada could not field a force of 12 AIP-propelled SSK modern submarines. Canada should seriously re-examine the need to acquire a bolstered fleet of new AIP submarines.

Notes

1. Canadian Coast Guard, Mission, Vision and Mandate, 2013, available at

www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca.

2. “Putin’s Russia in biggest Arctic military push since the fall of the Soviet Union,” National Post, 1 February 2017.

3. Head of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) Admiral Paul Maddison, testimony at Proceedings of Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence, Issue 4-Evidence Meeting of February 27, 2012.

4. Admiral Paul Maddison, Proceedings of Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence, Issue 4, Evidence Meeting of February 27, 2012.

5. Department of National Defence, Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy, Ottawa, 2017, pp. 60-61.

6. For a discussion of this, see Captain (N) Phil Webster, “Arctic Sovereignty, Submarine Operations and Water Space Management,” Canadian Naval Review, Volume 3, Number 3 (2007).

7. Admiral Paul Maddison Proceedings of Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence, Issue 4 - Evidence Meeting of February 27, 2012.

8. Department of National Defence, Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy, 2017, p. 34.

9. See Norman Jolin, “Future Canadian Submarine Capability: Some Considerations,” Canadian Naval Review, Vol. 11, No. 1 (2015), pp. 16-21.

10. For a good discussion of the different types of non-nuclear AIP systems, see Norman Jolin, “Future Canadian Submarine Capability: Some Considerations,” Canadian Naval Review, Vol. 11, No. 1 (2015), pp. 16-21.

11. Defence News, “Australia Chooses French Design for Future Submarine,” 26 April 2016.

12. The experience with the current submarines is instructive in this regard.

13. As recommended by the 2017 Senate Report on National Security and Defence. (Standing Senate Committee on National Security - Eleventh Report-Reinvesting in the Canadian Armed Forces: A Plan for the Future, pp. 37-38, Recommendation 13, 2017).

14. (Standing Senate Committee Report on National Security - Eleventh Report, Military Underfunded: “The Walk Must Match the Talk,” p. 21, Recommendation 2, 2017.

David K. Dunlop is a retired RCN Petty Officer 1st Class with over 41 years experience as a Tactical Data Coordinator.