You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Indian Armed Forces

- Thread starter Lieutenant

- Start date

from what I heard, India does things like this all the time. so the attention is diverted from the political failures going 'round in India. same thing with the MiG-21 downing an F-16, was just to divert the attention from political failures and to help keep Modi in power for another 5 years.Giving the public some spirit of hope?

Scorpion

THINK TANK: SENIOR

from what I heard, India does things like this all the time. so the attention is diverted from the political failures going 'round in India. same thing with the MiG-21 downing an F-16, was just to divert the attention from political failures and to help keep Modi in power for another 5 years.

Mr. Hugaholic knows how manipulate peoples emotions. I still want to see the shooting of the satellite he claimed happened few weeks ago.

Naval Officer Dies In Fire Onboard INS Vikramaditya In Karnataka

While the fire onborad INS Vikramaditya was brought under control, the naval officer lost consciousness due to the smoke and fumes during the firefighting efforts. Edited by Revathi Hariharan | Updated: April 26, 2019 15:48 IST

A Board of Inquiry to investigate the fire incident onboard INS Vikramaditya has been ordered.

Karwar, Karnataka:

A naval officer died today after a fire broke out onboard INS Vikramaditya, India's only aircraft carrier, while entering the harbor in Karnataka's Karwar.

"Lieutenant Commander DS Chauhan bravely led the firefighting efforts in the affected compartment," the Navy said in a statement.

While the fire was brought under control, the officer lost consciousness due to the smoke and fumes during the firefighting efforts. He was immediately evacuated to the Naval Hospital at Karwar but could not be revived, the Navy said.

The Navy added that the fire was brought under control by the ship's crew "in a swift action preventing any serious damage affecting the ship's combat capability."

INS Vikramaditya weighs 40,000 tonnes and is the biggest and heaviest ship in the Indian Navy.

A Board of Inquiry to investigate the fire incident has been ordered.

The $2.3 billion aircraft carrier came to India from Russia in January 2014. INS Vikramaditya, which was commissioned into the Indian Navy in November 2013 at the Sevmash shipyard in north Russia's Severodvinsk, is based at its home port at Karwar in Karnataka.

INS Vikramaditya is 284 metres long and 60 metres high -- that's about as high as a 20-storeyed building. The ship weighs 40,000 tonnes and is the biggest and heaviest ship in the Indian Navy.

www.ndtv.com

www.ndtv.com

While the fire onborad INS Vikramaditya was brought under control, the naval officer lost consciousness due to the smoke and fumes during the firefighting efforts. Edited by Revathi Hariharan | Updated: April 26, 2019 15:48 IST

A Board of Inquiry to investigate the fire incident onboard INS Vikramaditya has been ordered.

Karwar, Karnataka:

A naval officer died today after a fire broke out onboard INS Vikramaditya, India's only aircraft carrier, while entering the harbor in Karnataka's Karwar.

"Lieutenant Commander DS Chauhan bravely led the firefighting efforts in the affected compartment," the Navy said in a statement.

While the fire was brought under control, the officer lost consciousness due to the smoke and fumes during the firefighting efforts. He was immediately evacuated to the Naval Hospital at Karwar but could not be revived, the Navy said.

The Navy added that the fire was brought under control by the ship's crew "in a swift action preventing any serious damage affecting the ship's combat capability."

INS Vikramaditya weighs 40,000 tonnes and is the biggest and heaviest ship in the Indian Navy.

A Board of Inquiry to investigate the fire incident has been ordered.

The $2.3 billion aircraft carrier came to India from Russia in January 2014. INS Vikramaditya, which was commissioned into the Indian Navy in November 2013 at the Sevmash shipyard in north Russia's Severodvinsk, is based at its home port at Karwar in Karnataka.

INS Vikramaditya is 284 metres long and 60 metres high -- that's about as high as a 20-storeyed building. The ship weighs 40,000 tonnes and is the biggest and heaviest ship in the Indian Navy.

Naval Officer Dies In Fire Onboard INS Vikramaditya In Karnataka

A naval officer died today after a fire broke out onboard INS Vikramaditya when the aircraft carrier was entering the harbor in Karnataka's Karwar.

RIP what is the cause of the fire? India seems to have major issue in risk management.

View attachment 7031

bit.ly

bit.ly

View attachment 7032

Lt Commander DS Chauhan, "bravely led the firefighting efforts" that brought the blaze in the engine room under control swiftly to "prevent any serious damage" to the combat capabilities of the 44,500 tonne carrier, which which carries MiG-29K fighters and helicopters, said the Navy.

bit.ly

bit.ly

Fire on Indian carrier INS Vikramaditya kills officer

An Indian officer died on Friday after a fire broke out on board carrier INS Vikramaditya.

bit.ly

bit.ly

View attachment 7032

Lt Commander DS Chauhan, "bravely led the firefighting efforts" that brought the blaze in the engine room under control swiftly to "prevent any serious damage" to the combat capabilities of the 44,500 tonne carrier, which which carries MiG-29K fighters and helicopters, said the Navy.

Naval officer dies in fire onboard INS Vikramaditya | India News - Times of India

India News: Lt Commander DS Chauhan, 30-year-old officer, "bravely led the firefighting efforts" that brought the blaze in the engine room under control swiftly t

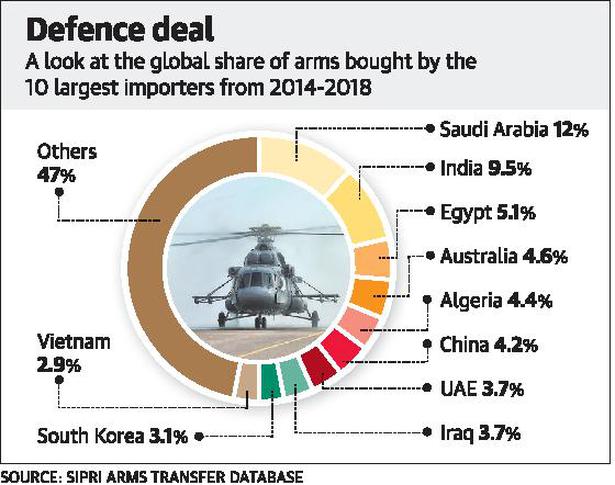

India is world’s second-largest arms importer

Special Correspondent

New Delhi,

March 11, 2019

Updated: March 12, 2019

Mi – 17 V5 Helicopter receives welcome shower during the induction ceremony at Safdarjung Airport on April 09, 2015. | File photo | Photo Credit: Prashant Nakwe

It cedes top spot to Saudi Arabia owing to 24% decrease between 2009-13 and 2014-18, partly due to delays in weapons delivery

India was the world’s second-largest arms importer from 2014-18, ceding the long-held tag as largest importer to Saudi Arabia, which accounted for 12% of the total imports during the period.

“India was the world’s second largest importer of major arms in 2014–18 and accounted for 9.5% of the global total,” according to the latest report published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) on Monday.

However, Indian imports decreased by 24% between 2009-13 and 2014-18, partly due to delays in deliveries of arms produced under licence from foreign suppliers, such as combat aircraft ordered from Russia in 2001 and submarines ordered from France in 2008, the report stated.

Russia accounted for 58% of Indian arms imports in 2014–18, compared with 76% in 2009-13. Israel, the U.S. and France all increased their arms exports to India in 2014-18. However, the Russian share in Indian imports is likely to go up sharply during the next five-year period as India signed several big-ticket deals recently, and more are in the pipeline.

These include S-400 air defence systems, four stealth frigates, AK-203 assault rifles, a second nuclear attack submarine on lease, and deals for Kamov-226T utility helicopters, Mi-17 helicopters and short-range air defence systems. The report noted that despite the long-standing conflict between India and Pakistan, arms imports decreased for both countries in 2014-18 compared with 2009-13.

Pakistan at 11th

Pakistan stood at the 11th position, accounting for 2.7% of all global imports. Its biggest source was China, from which 70% of arms were sourced, followed by the U.S. at 8.9% and, interestingly, Russia at 6%.

Globally, the volume of international transfers of major arms in 2014-18 was 7.8% higher than in 2009-13 and 23% higher than in 2004-2008. The five largest exporters in 2014-18 were the United States, Russia, France, Germany and China, which together accounted for 75% of the total volume of arms exports in 2014-18. “The flow of arms increased to the Middle East between 2009-13 and 2014-18, while there was a decrease in flows to all other regions,” the report said.

China, which has emerged as a major arms exporter, has increased its share by 2.7% for 2014-18 compared to 2009-13. Its biggest customers are Pakistan and Bangladesh.

As Indian imports reduced, Russian exports of major arms were dented, decreasing by 17% between 2009-13 and 2014-18. The report said this was partly due to “general reductions in Indian and Venezuelan arms imports”, which have been among the main recipients of Russian arms exports in previous years.

www.thehindu.com

www.thehindu.com

Special Correspondent

New Delhi,

March 11, 2019

Updated: March 12, 2019

Mi – 17 V5 Helicopter receives welcome shower during the induction ceremony at Safdarjung Airport on April 09, 2015. | File photo | Photo Credit: Prashant Nakwe

It cedes top spot to Saudi Arabia owing to 24% decrease between 2009-13 and 2014-18, partly due to delays in weapons delivery

India was the world’s second-largest arms importer from 2014-18, ceding the long-held tag as largest importer to Saudi Arabia, which accounted for 12% of the total imports during the period.

“India was the world’s second largest importer of major arms in 2014–18 and accounted for 9.5% of the global total,” according to the latest report published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) on Monday.

However, Indian imports decreased by 24% between 2009-13 and 2014-18, partly due to delays in deliveries of arms produced under licence from foreign suppliers, such as combat aircraft ordered from Russia in 2001 and submarines ordered from France in 2008, the report stated.

Russia accounted for 58% of Indian arms imports in 2014–18, compared with 76% in 2009-13. Israel, the U.S. and France all increased their arms exports to India in 2014-18. However, the Russian share in Indian imports is likely to go up sharply during the next five-year period as India signed several big-ticket deals recently, and more are in the pipeline.

These include S-400 air defence systems, four stealth frigates, AK-203 assault rifles, a second nuclear attack submarine on lease, and deals for Kamov-226T utility helicopters, Mi-17 helicopters and short-range air defence systems. The report noted that despite the long-standing conflict between India and Pakistan, arms imports decreased for both countries in 2014-18 compared with 2009-13.

Pakistan at 11th

Pakistan stood at the 11th position, accounting for 2.7% of all global imports. Its biggest source was China, from which 70% of arms were sourced, followed by the U.S. at 8.9% and, interestingly, Russia at 6%.

Globally, the volume of international transfers of major arms in 2014-18 was 7.8% higher than in 2009-13 and 23% higher than in 2004-2008. The five largest exporters in 2014-18 were the United States, Russia, France, Germany and China, which together accounted for 75% of the total volume of arms exports in 2014-18. “The flow of arms increased to the Middle East between 2009-13 and 2014-18, while there was a decrease in flows to all other regions,” the report said.

China, which has emerged as a major arms exporter, has increased its share by 2.7% for 2014-18 compared to 2009-13. Its biggest customers are Pakistan and Bangladesh.

As Indian imports reduced, Russian exports of major arms were dented, decreasing by 17% between 2009-13 and 2014-18. The report said this was partly due to “general reductions in Indian and Venezuelan arms imports”, which have been among the main recipients of Russian arms exports in previous years.

India is world’s second-largest arms importer

It cedes top spot to Saudi Arabia owing to 24% decrease between 2009-13 and 2014-18, partly due to delays in weapons delivery

Indian Navy orders 16 ASW shallow water craft

May 1, 2019

The Indian defense ministry has awarded shipbuilders M/s CSL and GRSE contracts for the construction of sixteen anti submarine warfare shallow water craft (ASW SWC).

Each shipyard will build 8 units with deliveries scheduled to start from October 2022. The shipyards are to hand over two ships per year after the first delivery.

These ASW SWC will displace 750 tons, develop speeds of 25 knots and will have a complement of 57.

According to earlier GRSE documents, the ships will measure around 70 meters with a maximum draught of 2.7 meter at full displacement.

The defense ministry said the craft would be capable of full-scale subsurface surveillance of coastal waters and coordinated ASW operations with aircraft. In addition, the vessels shall have the capability to interdict and destroy subsurface targets in coastal waters.

In their secondary role, these will be capable to prosecute intruding aircraft, and lay mines in the sea bed.

navaltoday.com

navaltoday.com

May 1, 2019

The Indian defense ministry has awarded shipbuilders M/s CSL and GRSE contracts for the construction of sixteen anti submarine warfare shallow water craft (ASW SWC).

Each shipyard will build 8 units with deliveries scheduled to start from October 2022. The shipyards are to hand over two ships per year after the first delivery.

These ASW SWC will displace 750 tons, develop speeds of 25 knots and will have a complement of 57.

According to earlier GRSE documents, the ships will measure around 70 meters with a maximum draught of 2.7 meter at full displacement.

The defense ministry said the craft would be capable of full-scale subsurface surveillance of coastal waters and coordinated ASW operations with aircraft. In addition, the vessels shall have the capability to interdict and destroy subsurface targets in coastal waters.

In their secondary role, these will be capable to prosecute intruding aircraft, and lay mines in the sea bed.

Indian Navy orders 16 ASW shallow water craft

The Indian defense ministry has awarded shipbuilders M/s CSL and GRSE contracts for the construction of sixteen anti submarine warfare shallow water craft (ASW SWC). Each shipyard will build 8 units with deliveries scheduled to start from October 2022. The shipyards are to hand over two ships...

GRSE signs contract for 8 anti-submarine warfare shallow water crafts for Indian Navy

The vessels can be deployed for search and rescue by day and night in coastal areas. In their secondary role, they will be capable to prosecute intruding aircraft, and lay mines in the seabed.

By Anuradha Himatsin

29.04.2019

KOLKATA: Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Limited (GRSENSE 12.54 %) and India’s defence ministry signed a contract on Monday for construction and supply of eight anti-submarine warfare shallow water crafts (ASWSWCs) for Indian Navy.

The order value for these eight vessels is pegged at Rs 6311.32 crore. The first ship is to be delivered within 42 months from contract signing date and subsequent balance ships delivery schedule will be two ships per year. The project will have to completed within 84 months from date of signing the contract.

GRSE is currently handling major projects including building 3 stealth frigates for Indian Navy under P17A project, ASW Corvettes for Indian Navy, LCUs for Indian Navy, 4 survey vessels (large) for Indian Navy, FPVs for Indian Coast Guard etc. The warships built by GRSE ranges from advanced frigates to anti-submarine warfare corvettes to fleet tankers, fast attack

crafts, etc.

The present project will further consolidate GRSE’s position as a shipyardNSE -3.45 % with all round capability to design and build ASWSWC warships with state-of-the-art-technology, the GRSE release stated.

Incidentally, "these anti-submarine warfare shallow water crafts are designed for a deep displacement of 750 tonne, speed of 25 knots and complement of 57 and capable of full scale sub surface surveillance of coastal waters, SAU and coordinated ASW operations with aircraft,” the media statement added.

In addition, the vessels will have the capability to interdict/destroy sub surface targets in coastal waters. They can also be deployed for search and rescue by day and night in coastal areas. In their secondary role, they will be capable to prosecute intruding aircraft, and lay mines in the sea bed.

The vessels will be equipped with highly advanced state-of-the-art integrated platform management systems including propulsion machinery, auxiliary machinery, power generation and distribution machinery and damage control machinery etc. The warships will conform to latest MARPOL (Marine Pollution) Standards of the International Maritime Organization and Safety of Life at Sea.

The design and construction of these ships at GRSE is another significant milestone in the ‘Make In India’ initiative of the government of India.

GRSE signs contract for 8 anti-submarine warfare shallow water crafts for Indian Navy

The vessels can be deployed for search and rescue by day and night in coastal areas. In their secondary role, they will be capable to prosecute intruding aircraft, and lay mines in the seabed.

By Anuradha Himatsin

29.04.2019

KOLKATA: Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Limited (GRSENSE 12.54 %) and India’s defence ministry signed a contract on Monday for construction and supply of eight anti-submarine warfare shallow water crafts (ASWSWCs) for Indian Navy.

The order value for these eight vessels is pegged at Rs 6311.32 crore. The first ship is to be delivered within 42 months from contract signing date and subsequent balance ships delivery schedule will be two ships per year. The project will have to completed within 84 months from date of signing the contract.

GRSE is currently handling major projects including building 3 stealth frigates for Indian Navy under P17A project, ASW Corvettes for Indian Navy, LCUs for Indian Navy, 4 survey vessels (large) for Indian Navy, FPVs for Indian Coast Guard etc. The warships built by GRSE ranges from advanced frigates to anti-submarine warfare corvettes to fleet tankers, fast attack

crafts, etc.

The present project will further consolidate GRSE’s position as a shipyardNSE -3.45 % with all round capability to design and build ASWSWC warships with state-of-the-art-technology, the GRSE release stated.

Incidentally, "these anti-submarine warfare shallow water crafts are designed for a deep displacement of 750 tonne, speed of 25 knots and complement of 57 and capable of full scale sub surface surveillance of coastal waters, SAU and coordinated ASW operations with aircraft,” the media statement added.

In addition, the vessels will have the capability to interdict/destroy sub surface targets in coastal waters. They can also be deployed for search and rescue by day and night in coastal areas. In their secondary role, they will be capable to prosecute intruding aircraft, and lay mines in the sea bed.

The vessels will be equipped with highly advanced state-of-the-art integrated platform management systems including propulsion machinery, auxiliary machinery, power generation and distribution machinery and damage control machinery etc. The warships will conform to latest MARPOL (Marine Pollution) Standards of the International Maritime Organization and Safety of Life at Sea.

The design and construction of these ships at GRSE is another significant milestone in the ‘Make In India’ initiative of the government of India.

GRSE signs contract for 8 anti-submarine warfare shallow water crafts for Indian Navy

15 Indian commandos, driver killed in Maoist attack

May 01, 2019

Maoists attacked the commandos travelling in a vehicle to inspect an earlier attack

AFP

Mangled remains of a police vehicle, carrying security personnel that was allegedly blasted by Maoists using IED, in Gadchiroli, Wednesday, May 1, 2019.

Image Credit: PTI

Mumbai: A suspected bomb attack by Maoist rebels killed 15 Indian elite commandos and their driver on Wednesday, police said, the latest incident of election-time violence in a decades-long insurgency.

"Maoists attacked a team of commandos travelling in a private vehicle to inspect an earlier attack. So far 16 men have died," an official at police headquarters in the western state of Maharashtra told AFP.

"More teams have been sent to site for rescue and combat operations," said the officer, who did not want to give his name.

India is holding elections and attacks by Maoist rebels, who are active in several states, often spike as the country goes to the polls.

A second police official put the death toll in the latest incident in the Gadchiroli region of Maharashtra at 15.

"Maoists torched over 30 vehicles in Gadchiroli today at 12.30pm (0700 GMT). In another blast, 15 security officers were killed and rescue operations are ongoing to ascertain the damage," Gadchiroli police official Prashant Dute told AFP.

Indian forces have been fighting Maoists rebels for decades in several areas, in an insurgency that has killed tens of thousands.

Image Credit: Twitter

The Maoists are believed to be present in at least 20 Indian states but are most active in Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bihar, Jharkhand - and Maharashtra.

India's nationwide election began on April 11 and runs until May 19.

Last weekend rebels opened fire on Indian police, killing two constables and wounding a villager in the central state of Chhattisgarh, the Press Trust of India (PTI) news agency reported.

One constable and an assistant constable died at the scene and the villager, shot in the chest, was taken by local residents for treatment, PTI reported.

A roadside bomb attack on a political convoy in early April killed five people in Chhattisgarh, two days before the world's biggest election began.

Modi condemns

Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Wednesday swiftly condemned the latest attack.

"Strongly condemn the despicable attack on our security personnel in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra. I salute all the brave personnel," Modi tweeted.

"Their sacrifices will never be forgotten. My thoughts & solidarity are with the bereaved families. The perpetrators of such violence will not be spared," he added.

Devendra Fadnavis, chief minister of Maharashtra and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) ally of Modi, confirmed the attack on Twitter.

"Anguished to know that our 16 police personnel from Gadchiroli C-60 force got martyred in a cowardly attack by naxals (Maoists) today. My thoughts and prayers are with the martyrs' families," Fadnavis said.

Home Minister Rajnath Singh called the attack "an act of cowardice and desperation".

"We are extremely proud of the valour of our police personnel," he said. "Their supreme sacrifice while serving the nation will not go in vain."

May 01, 2019

Maoists attacked the commandos travelling in a vehicle to inspect an earlier attack

AFP

Mangled remains of a police vehicle, carrying security personnel that was allegedly blasted by Maoists using IED, in Gadchiroli, Wednesday, May 1, 2019.

Image Credit: PTI

Mumbai: A suspected bomb attack by Maoist rebels killed 15 Indian elite commandos and their driver on Wednesday, police said, the latest incident of election-time violence in a decades-long insurgency.

"Maoists attacked a team of commandos travelling in a private vehicle to inspect an earlier attack. So far 16 men have died," an official at police headquarters in the western state of Maharashtra told AFP.

"More teams have been sent to site for rescue and combat operations," said the officer, who did not want to give his name.

#JustIn -- 16 dead in the deadly Maoist attack on a team of C60 Commandos in Maharashtra's Gadchiroli. | #GadchiroliNaxalAttack pic.twitter.com/K807wTwFSY

— News18 (@CNNnews18) May 1, 2019

India is holding elections and attacks by Maoist rebels, who are active in several states, often spike as the country goes to the polls.

A second police official put the death toll in the latest incident in the Gadchiroli region of Maharashtra at 15.

"Maoists torched over 30 vehicles in Gadchiroli today at 12.30pm (0700 GMT). In another blast, 15 security officers were killed and rescue operations are ongoing to ascertain the damage," Gadchiroli police official Prashant Dute told AFP.

Indian forces have been fighting Maoists rebels for decades in several areas, in an insurgency that has killed tens of thousands.

Image Credit: Twitter

The Maoists are believed to be present in at least 20 Indian states but are most active in Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bihar, Jharkhand - and Maharashtra.

India's nationwide election began on April 11 and runs until May 19.

Last weekend rebels opened fire on Indian police, killing two constables and wounding a villager in the central state of Chhattisgarh, the Press Trust of India (PTI) news agency reported.

One constable and an assistant constable died at the scene and the villager, shot in the chest, was taken by local residents for treatment, PTI reported.

A roadside bomb attack on a political convoy in early April killed five people in Chhattisgarh, two days before the world's biggest election began.

Modi condemns

Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Wednesday swiftly condemned the latest attack.

"Strongly condemn the despicable attack on our security personnel in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra. I salute all the brave personnel," Modi tweeted.

"Their sacrifices will never be forgotten. My thoughts & solidarity are with the bereaved families. The perpetrators of such violence will not be spared," he added.

Devendra Fadnavis, chief minister of Maharashtra and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) ally of Modi, confirmed the attack on Twitter.

"Anguished to know that our 16 police personnel from Gadchiroli C-60 force got martyred in a cowardly attack by naxals (Maoists) today. My thoughts and prayers are with the martyrs' families," Fadnavis said.

Home Minister Rajnath Singh called the attack "an act of cowardice and desperation".

"We are extremely proud of the valour of our police personnel," he said. "Their supreme sacrifice while serving the nation will not go in vain."

15 Indian commandos, driver killed in Maoist attack

Maoists attacked the commandos travelling in a vehicle to inspect an earlier attack

gulfnews.com

Maoists kill 15 Indian elite commandos

AFP

May 02, 2019

MUMBAI: A bomb attack by suspected Maoist rebels killed 15 Indian elite commandos and their driver on Wednesday, police said, in the latest incident of election-time violence in a decades-long insurgency.

Tens of thousands of people have been killed since the 1960s in several areas of India in clashes between security forces and guerrillas first inspired by Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Zedong.

In the latest incident, “Maoists attacked a team of commandos travelling in a private vehicle to inspect an earlier attack. So far 16 men have died,” an official at police headquarters in the western state of Maharashtra said.

The attack, the deadliest carried out by the Maoists since 2017, happened in the densely forested Gadchiroli region of Maharashtra, deep in the Indian interior.

Gadchiroli police official Prashant Dute said that the police commandos had been on their way to the scene of the earlier attack in the same area in which more than 30 vehicles were torched.

The Maoists insurgents are believed to be present in at least 20 Indian states but are most active in Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bihar and Jharkhand.

Thousands of armed men and women — also known as Naxals — say they are fighting for the rights of indigenous tribal people, including for land, resources and jobs.

India’s current election began on April 11 and is due to run until May 19.

Attacks by Maoist rebels often spike as the country goes to the polls.

Last weekend rebels opened fire on Indian police, killing two constables and wounding a villager in the central state of Chhattisgarh, the Press Trust of India (PTI) news agency reported.

One constable and an assistant constable died at the scene and the villager, shot in the chest, was taken by local residents for treatment, PTI reported.

A roadside bomb attack on a political convoy in early April killed five people in Chhattisgarh, two days before the world’s biggest election began.

The rebels often call for a boycott of elections as part of their campaign against the Indian state.

The Gadchiroli district, some 900 kilometres east of state capital Mumbai, has long been a hotbed of violence, with at least 17 police killed there in 2009.

It is a key transit point for the guerrillas, connecting western India with central and southern states in a restive tranche known as the “red corridor”.

On April 11, the day voting began, a landmine planted by Maoists exploded near a polling centre there. There were no injuries.

In April 2018, raids on rebel camps in the region killed at least 37 insurgents, police said. Many of the slain rebels were women, police said.

Wednesday’s attack was the deadliest by Maoists in India since 2017 when at least 25 paramilitaries were killed in the Sukma district of central Chhattisgarh state.

AFP

May 02, 2019

MUMBAI: A bomb attack by suspected Maoist rebels killed 15 Indian elite commandos and their driver on Wednesday, police said, in the latest incident of election-time violence in a decades-long insurgency.

Tens of thousands of people have been killed since the 1960s in several areas of India in clashes between security forces and guerrillas first inspired by Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Zedong.

In the latest incident, “Maoists attacked a team of commandos travelling in a private vehicle to inspect an earlier attack. So far 16 men have died,” an official at police headquarters in the western state of Maharashtra said.

The attack, the deadliest carried out by the Maoists since 2017, happened in the densely forested Gadchiroli region of Maharashtra, deep in the Indian interior.

Gadchiroli police official Prashant Dute said that the police commandos had been on their way to the scene of the earlier attack in the same area in which more than 30 vehicles were torched.

The Maoists insurgents are believed to be present in at least 20 Indian states but are most active in Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bihar and Jharkhand.

Thousands of armed men and women — also known as Naxals — say they are fighting for the rights of indigenous tribal people, including for land, resources and jobs.

India’s current election began on April 11 and is due to run until May 19.

Attacks by Maoist rebels often spike as the country goes to the polls.

Last weekend rebels opened fire on Indian police, killing two constables and wounding a villager in the central state of Chhattisgarh, the Press Trust of India (PTI) news agency reported.

One constable and an assistant constable died at the scene and the villager, shot in the chest, was taken by local residents for treatment, PTI reported.

A roadside bomb attack on a political convoy in early April killed five people in Chhattisgarh, two days before the world’s biggest election began.

The rebels often call for a boycott of elections as part of their campaign against the Indian state.

The Gadchiroli district, some 900 kilometres east of state capital Mumbai, has long been a hotbed of violence, with at least 17 police killed there in 2009.

It is a key transit point for the guerrillas, connecting western India with central and southern states in a restive tranche known as the “red corridor”.

On April 11, the day voting began, a landmine planted by Maoists exploded near a polling centre there. There were no injuries.

In April 2018, raids on rebel camps in the region killed at least 37 insurgents, police said. Many of the slain rebels were women, police said.

Wednesday’s attack was the deadliest by Maoists in India since 2017 when at least 25 paramilitaries were killed in the Sukma district of central Chhattisgarh state.

Maoists kill 15 Indian elite commandos

MUMBAI: A bomb attack by suspected Maoist rebels killed 15 Indian elite commandos and their driver on Wednesday,...

www.dawn.com

Army raises alarm over rising accidents due to faulty ammunition

Rajat Pandit | TNN | Updated: May 14, 2019

View attachment 7201

The Army has sounded an alarm over the unacceptably high number of accidents taking place in the field due to poor quality and defective ammunition being supplied for tanks, artillery, air defence and other guns by the state-owned Ordnance Factory Board (OFB).The Army has told the defence ministry (MoD) that the spike in ammunition-related accidents is causing “fatalities, injuries and damage to equipment” at an alarming rate. This, in turn, is “leading to the Army’s loss of confidence in most types of ammunition” being manufactured by OFB, sources said.

They said the Army had raised with secretary (defence production) Ajay Kumar the “serious concerns” about the lack of requisite “quality control and quality assurance” by OFB, which, with 41 factories and an annual turnover of about Rs 19,000 crore, is the main source of arms and ammunition to the over 12-lakh-strong force. “Any drop in the quality of OFB products has major operational ramifications on the country’s war-waging potential,” a source said.

The red alert has led to “an urgent collaborative effort” between the Army and MoD’s department of defence production to improve the functioning of OFB, with Kumar also asking the force to submit “a paper” about different problems with the ammunition.

The 15-page paper presents an extremely grim picture. It says “regular accidents” are occurring with 105mm Indian field guns, 105mm light field guns, 130mm MA1 medium guns, 40mm L-70 air defence guns and the main guns of T-72, T-90 and Arjun battle tanks, with some “isolated cases” also being reported from 155mm Bofors guns due to defective ammunition. “With OFB’s piecemeal and poor approach to problem-solving, the Army has stopped firing some long-range ammunition,” said a source.

“With the OFB’s piecemeal and poor approach in problem-solving, the Army has stopped firing some types of long-range ammunition, while also refraining from not testing some others to their maximum ranges. There have been, for instance, over 40 accidents of the 125mm high explosive ammunition fired by tanks in the last five years,” said a source.

Similarly, the Army has stopped “all training firing” of the 40mm high explosive ammunition by the L-70 air defence guns after the latest accident in February, in which an officer and four soldiers were seriously injured at the Mahajan field firing range. “The entire range of the L-70 high explosive ammunition held by the Army is now suspect,” said another source.

Moreover, a large quantum of OFB ammunition has also been found defective during their shelf-lives due to poor quality control. “Blackening of ammunition of small arms and heavy-caliber ammunition due to poor metallurgy and packaging is also a major problem,” said the source.

American officials, incidentally, had also blamed OFB ammunition after the muzzle of a new M-777 ultra-light howitzer had broken during tests at the Pokhran field firing ranges in September 2017 before the Army began the induction of 145 such artillery guns from the US under a Rs 5,000 crore deal. “A joint team had later scientifically traced the problem to a particular lot of bi-modular charge system ammunition…it was addressed. But the overall problems remain,” he added.

OFB’s defence

The OFB, on being contacted by TOI, said ammunition is supplied to Army only after stringent inspection by the factory’s quality control department as well as the DGQA (directorate general of quality assurance). An ammo batch is issued only after it passes extensive tests, ranging from “all input material” being tested in designated labs to “100% dimensional checking” in the factory, said an official.

Some defects or accidents, however, do sometimes occur during “bulk exploitation” of the ammunition by the Army. “The important reasons can be manufacturing deficiencies, improper handling and storage in ammo depots, improper maintenance of weapon systems, and improper handling of ammo and weapons during firings,” he said.

“The OFB is not aware of the storage/handling/maintenance conditions at the Army’s end, which are equally responsible for defects/accidents.” The OFB has implemented recommendations of seven committees but “the drills and condition of weapons were never investigated,” he said.

timesofindia.indiatimes.com

timesofindia.indiatimes.com

Rajat Pandit | TNN | Updated: May 14, 2019

View attachment 7201

The Army has sounded an alarm over the unacceptably high number of accidents taking place in the field due to poor quality and defective ammunition being supplied for tanks, artillery, air defence and other guns by the state-owned Ordnance Factory Board (OFB).The Army has told the defence ministry (MoD) that the spike in ammunition-related accidents is causing “fatalities, injuries and damage to equipment” at an alarming rate. This, in turn, is “leading to the Army’s loss of confidence in most types of ammunition” being manufactured by OFB, sources said.

They said the Army had raised with secretary (defence production) Ajay Kumar the “serious concerns” about the lack of requisite “quality control and quality assurance” by OFB, which, with 41 factories and an annual turnover of about Rs 19,000 crore, is the main source of arms and ammunition to the over 12-lakh-strong force. “Any drop in the quality of OFB products has major operational ramifications on the country’s war-waging potential,” a source said.

The red alert has led to “an urgent collaborative effort” between the Army and MoD’s department of defence production to improve the functioning of OFB, with Kumar also asking the force to submit “a paper” about different problems with the ammunition.

The 15-page paper presents an extremely grim picture. It says “regular accidents” are occurring with 105mm Indian field guns, 105mm light field guns, 130mm MA1 medium guns, 40mm L-70 air defence guns and the main guns of T-72, T-90 and Arjun battle tanks, with some “isolated cases” also being reported from 155mm Bofors guns due to defective ammunition. “With OFB’s piecemeal and poor approach to problem-solving, the Army has stopped firing some long-range ammunition,” said a source.

“With the OFB’s piecemeal and poor approach in problem-solving, the Army has stopped firing some types of long-range ammunition, while also refraining from not testing some others to their maximum ranges. There have been, for instance, over 40 accidents of the 125mm high explosive ammunition fired by tanks in the last five years,” said a source.

Similarly, the Army has stopped “all training firing” of the 40mm high explosive ammunition by the L-70 air defence guns after the latest accident in February, in which an officer and four soldiers were seriously injured at the Mahajan field firing range. “The entire range of the L-70 high explosive ammunition held by the Army is now suspect,” said another source.

Moreover, a large quantum of OFB ammunition has also been found defective during their shelf-lives due to poor quality control. “Blackening of ammunition of small arms and heavy-caliber ammunition due to poor metallurgy and packaging is also a major problem,” said the source.

American officials, incidentally, had also blamed OFB ammunition after the muzzle of a new M-777 ultra-light howitzer had broken during tests at the Pokhran field firing ranges in September 2017 before the Army began the induction of 145 such artillery guns from the US under a Rs 5,000 crore deal. “A joint team had later scientifically traced the problem to a particular lot of bi-modular charge system ammunition…it was addressed. But the overall problems remain,” he added.

OFB’s defence

The OFB, on being contacted by TOI, said ammunition is supplied to Army only after stringent inspection by the factory’s quality control department as well as the DGQA (directorate general of quality assurance). An ammo batch is issued only after it passes extensive tests, ranging from “all input material” being tested in designated labs to “100% dimensional checking” in the factory, said an official.

Some defects or accidents, however, do sometimes occur during “bulk exploitation” of the ammunition by the Army. “The important reasons can be manufacturing deficiencies, improper handling and storage in ammo depots, improper maintenance of weapon systems, and improper handling of ammo and weapons during firings,” he said.

“The OFB is not aware of the storage/handling/maintenance conditions at the Army’s end, which are equally responsible for defects/accidents.” The OFB has implemented recommendations of seven committees but “the drills and condition of weapons were never investigated,” he said.

Indian Army raises alarm over rising accidents due to faulty ammunition | India News - Times of India

India News: The Army has sounded an alarm over the high number of accidents taking place in the field due to defective ammunition being supplied for tanks, artill

India to buy Russian S-400 missile system

Sunday, May 26, 2019

Indian authorities decided to buy S-400 missile system from Russia since these systems are used in China, reports Moneycontrol news website.

According to the publication, India doesn't intend to use the Russian S-400 missile system for defense purposes but plans to research their tactical and technical capabilities. The country also plans to test its Rafale fighter aircraft — in particular, their ability to penetrate China's airspace, which is protected by the S-400 missile systems.

Also, it is noted that the refusal of New Delhi to develop an aircraft fighter based on Su-57 in cooperation with Russia "seriously hit the budget of the Russian industry."

The contract with India for the supply of S-400 Triumph missile systems with a cost of more than $5 billion was signed in October 2018. India will receive five regimental sets of the system. The first one of them should be delivered to the country in the autumn of 2020.

uawire.org

uawire.org

Sunday, May 26, 2019

Indian authorities decided to buy S-400 missile system from Russia since these systems are used in China, reports Moneycontrol news website.

According to the publication, India doesn't intend to use the Russian S-400 missile system for defense purposes but plans to research their tactical and technical capabilities. The country also plans to test its Rafale fighter aircraft — in particular, their ability to penetrate China's airspace, which is protected by the S-400 missile systems.

Also, it is noted that the refusal of New Delhi to develop an aircraft fighter based on Su-57 in cooperation with Russia "seriously hit the budget of the Russian industry."

The contract with India for the supply of S-400 Triumph missile systems with a cost of more than $5 billion was signed in October 2018. India will receive five regimental sets of the system. The first one of them should be delivered to the country in the autumn of 2020.

India to buy Russian S-400 missile system

Indian authorities decided to buy S-400 missile system from Russia since these systems are used in China, reports Moneycontrol news website. According to the publication, India doesn't intend to use the Russian S-400 missile system for defense purposes but plans to research their tactical and...

Indian Army to Recruit Women as Military Police

View attachment 7453

The small step forward highlights just how far women have to go to achieve gender parity in the Indian armed forces.

As a step to open up new avenues for women, the Indian Army issued a formal notification on April 25, 2019 inviting female applicants for the position of Soldier General Duty. These appointments are to take place under the Personnel Below Officer Rank (PBOR) category within the military police.

Those selected will be responsible for investigating offenses such as molestation, theft, and rape; preventing the breach of rules and regulations by army personnel; providing assistance to civil police; and carrying out ceremonial duties.

While the decision brings with it an opportunity for women to be recruited in combat-support operations, women appearing in frontline combat roles such as infantry, artillery, and armored units remains a distant reality. This restricted involvement begs the question as to wether women’s participation in the PBOR can really be viewed as an exemplary initiative targeted toward achieving gender parity within the Indian armed forces.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Women’s Visibility in the Army

The Indian Army’s experience of long-term employment and management of women officers has been limited. As of January 2019, the Indian Army — which is the second largest in the world — had women making up just 3.80 percent of its workforce. There were 1,561 women officers as compared to 41,074 male counterparts.

The army initially began inducting women as officers in 1992 through Short Service Commissions (SSC) with a preliminary term of engagement for five years, which was later extended to 10 years with an option of further extension by four years. However, no additional opportunities were created thereafter to facilitate women’s employment across other divisions of the army. In fact, these women have essentially been confined to auxiliary roles in the education, medical, engineering, signals, legal, and military intelligence wings.

It was only in 2008 that the army granted Permanent Commissions (PC) to some women officers within the Army Education Corps and Judge Advocate General departments — allowing them to serve until the age of retirement. But due to the predominance of patriarchal ideologies, the army has been marred by controversies regarding the grant and extending permission to women to control certain units.

During his 72nd Independence Day address, Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi announced that women officers with SSCs in the Indian Armed Forces would be eligible for PCs through a transparent selection process. As a result, women now also have the option of taking up PCs in all the 10 branches of the Indian Army where they are already being inducted as officers under SSC.

The PBOR recruitment is therefore the first time in more than two decades that women are being recruited by the army in other ranks and not only as officers but as soldiers, offering them more active military duties and an opportunity to be posted in high-risk areas.

An Instance of Women Empowerment?

Although a leap forward, the decision to employ women as corps of the military police cannot really be considered as a milestone for women empowerment, as the doors have opened up with an extremely limited capacity.

The fundamental caveat here is that women’s position within the army might improve with their entry into the PBOR category but even as soldiers they will continue to be placed in less-challenging peripheral roles — once again barring them from multifarious combat tasks and restraining their prospects for diversification beyond a civilizing force. This is in stark contrast to their male counterparts, who are bestowed with unrestricted opportunities for capacity development in all ranks of the army; sufficient deployment options to hazardous and difficult combat zones; and privileges of greater institutional powers.

Consequently, the move to recruit women into the combatant support arm of the military alone is discriminatory and a compromise of women’s dignity and freedom of choice to be placed in the direct line of action. Such regressive gender disparities are well reflected in the institutional attitudes right at the top — recently made evident by Army Chief Bipin Rawat. In an interview, he provided sociological and logistical explanations for the army’s inability to recruit women in combat operations.

Second, as a part of this initiative, the army plans to induct 800 women in all — with a yearly intake of 52 personnel — to eventually form 20 percent of the total corps of military police. This also means that the remaining 80 percent of positions has by default been reserved for men. The proportion is therefore extremely dismal. According to the 2019 World Population Review, about 48.50 percent of Indians are women, nearly half of the total population. This raises an important question: why is women’s participation in the army being limited to a percentage far below India’s actual population divide?

Third, women’s recruitment within the PBOR category is conditioned upon the fact that the candidate must be an unmarried female and they “must undertake not to marry until they complete their full training” — making this a classic case where entrenched social institutions like marriage act as an obstruction to women’s professional empowerment. Such parameters are further demonstrative of a failure to recognize women as independent agents in their own rights and in control of their destiny.

Conclusion

The entire discourse on India’s national security is shaped, limited, and permeated by ideas about gender — with an overt masculine predominance and the structural exclusion of women. Resultantly, the army, particularly the combat forces, are considered the exclusive domain of men. It is therefore not at all surprising that women are constantly kept outside the direct line of action.

Viewed in light of this narrative, the decision to include women as soldiers in the Indian Army is a historic one and offers some cause of celebration. But to achieve the genuine promotion of women’s right and gender equality, it is important to provide female officers with the option to serve in hazardous and difficult roles, and the chance to receive consideration for same opportunities as their male counterparts. It is time to deconstruct toxic gendered and patriarchal biases and recognize the competence of women to protect national security.

View attachment 7453

The small step forward highlights just how far women have to go to achieve gender parity in the Indian armed forces.

As a step to open up new avenues for women, the Indian Army issued a formal notification on April 25, 2019 inviting female applicants for the position of Soldier General Duty. These appointments are to take place under the Personnel Below Officer Rank (PBOR) category within the military police.

Those selected will be responsible for investigating offenses such as molestation, theft, and rape; preventing the breach of rules and regulations by army personnel; providing assistance to civil police; and carrying out ceremonial duties.

While the decision brings with it an opportunity for women to be recruited in combat-support operations, women appearing in frontline combat roles such as infantry, artillery, and armored units remains a distant reality. This restricted involvement begs the question as to wether women’s participation in the PBOR can really be viewed as an exemplary initiative targeted toward achieving gender parity within the Indian armed forces.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Women’s Visibility in the Army

The Indian Army’s experience of long-term employment and management of women officers has been limited. As of January 2019, the Indian Army — which is the second largest in the world — had women making up just 3.80 percent of its workforce. There were 1,561 women officers as compared to 41,074 male counterparts.

The army initially began inducting women as officers in 1992 through Short Service Commissions (SSC) with a preliminary term of engagement for five years, which was later extended to 10 years with an option of further extension by four years. However, no additional opportunities were created thereafter to facilitate women’s employment across other divisions of the army. In fact, these women have essentially been confined to auxiliary roles in the education, medical, engineering, signals, legal, and military intelligence wings.

It was only in 2008 that the army granted Permanent Commissions (PC) to some women officers within the Army Education Corps and Judge Advocate General departments — allowing them to serve until the age of retirement. But due to the predominance of patriarchal ideologies, the army has been marred by controversies regarding the grant and extending permission to women to control certain units.

During his 72nd Independence Day address, Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi announced that women officers with SSCs in the Indian Armed Forces would be eligible for PCs through a transparent selection process. As a result, women now also have the option of taking up PCs in all the 10 branches of the Indian Army where they are already being inducted as officers under SSC.

The PBOR recruitment is therefore the first time in more than two decades that women are being recruited by the army in other ranks and not only as officers but as soldiers, offering them more active military duties and an opportunity to be posted in high-risk areas.

An Instance of Women Empowerment?

Although a leap forward, the decision to employ women as corps of the military police cannot really be considered as a milestone for women empowerment, as the doors have opened up with an extremely limited capacity.

The fundamental caveat here is that women’s position within the army might improve with their entry into the PBOR category but even as soldiers they will continue to be placed in less-challenging peripheral roles — once again barring them from multifarious combat tasks and restraining their prospects for diversification beyond a civilizing force. This is in stark contrast to their male counterparts, who are bestowed with unrestricted opportunities for capacity development in all ranks of the army; sufficient deployment options to hazardous and difficult combat zones; and privileges of greater institutional powers.

Consequently, the move to recruit women into the combatant support arm of the military alone is discriminatory and a compromise of women’s dignity and freedom of choice to be placed in the direct line of action. Such regressive gender disparities are well reflected in the institutional attitudes right at the top — recently made evident by Army Chief Bipin Rawat. In an interview, he provided sociological and logistical explanations for the army’s inability to recruit women in combat operations.

Second, as a part of this initiative, the army plans to induct 800 women in all — with a yearly intake of 52 personnel — to eventually form 20 percent of the total corps of military police. This also means that the remaining 80 percent of positions has by default been reserved for men. The proportion is therefore extremely dismal. According to the 2019 World Population Review, about 48.50 percent of Indians are women, nearly half of the total population. This raises an important question: why is women’s participation in the army being limited to a percentage far below India’s actual population divide?

Third, women’s recruitment within the PBOR category is conditioned upon the fact that the candidate must be an unmarried female and they “must undertake not to marry until they complete their full training” — making this a classic case where entrenched social institutions like marriage act as an obstruction to women’s professional empowerment. Such parameters are further demonstrative of a failure to recognize women as independent agents in their own rights and in control of their destiny.

Conclusion

The entire discourse on India’s national security is shaped, limited, and permeated by ideas about gender — with an overt masculine predominance and the structural exclusion of women. Resultantly, the army, particularly the combat forces, are considered the exclusive domain of men. It is therefore not at all surprising that women are constantly kept outside the direct line of action.

Viewed in light of this narrative, the decision to include women as soldiers in the Indian Army is a historic one and offers some cause of celebration. But to achieve the genuine promotion of women’s right and gender equality, it is important to provide female officers with the option to serve in hazardous and difficult roles, and the chance to receive consideration for same opportunities as their male counterparts. It is time to deconstruct toxic gendered and patriarchal biases and recognize the competence of women to protect national security.

Scorpion

THINK TANK: SENIOR

Good going. Women should take their part in the society

This is might be a bit of a problem. Why they want to throw women in front lines?

it is important to provide female officers with the option to serve in hazardous and difficult roles,

This is might be a bit of a problem. Why they want to throw women in front lines?